The Sioux are a diverse group of tribes most easily identified by their related languages. This group, which extends across three geographically and culturally distinct divisions, comprises the Siouan language family (DeMallie 2001). These divisions were recognized by the U.S. government in the early nineteenth century and included the Santee Sioux who consider themselves Dakota, and are divided into four smaller bands known as the Mdewankantonwon, Wahpeton, Wahpekute, and the Sisseton; the Yankton/Yanktonai Sioux, who split from the Dakota and moved on to the Plains region, and comprised three bands known as the Yankton, Upper Yanktonai, and the Lower Yanktonai; and the Teton Sioux, who consider themselves Lakota, who moved west of the Missouri River and occupied portions of the northeastern Powder River Basin, and are comprised of seven bands known as the Oglala, Miniconjou, Sicangu or Brulé, Hunkpapa, Sihasapa or Blackfoot, Itazipacola or Sans Arc, and the Oohenupa or Two Kettle (Gagnon and White Eyes 1992). Although the Sioux language contains variations, these are dialectically distinct and considered mutually intelligible to each other.

Historic descriptions of the Sioux territory emphasize the vast expanses the tribe inhabited. The Sioux are documented as occupying the region extending from Mille Lacs to the Missouri River as early as 1640. Denig noted that within the borders of the Sioux nation was Turtle Mountain, Pembinar River, the “Grand River of the Arickaras,” Powder River, the Black Hills, Big Sioux River, and Vermillion River (Denig 1961:3). Early accounts of the Sioux are based on linguistic distribution patterns that have placed them west of Lake Michigan, and in parts of southern Wisconsin, southeastern Minnesota, northeastern Iowa, and northern Illinois (DeMallie 2001).

Each division of Sioux usually occupied, to varying degrees, specific territories. The Teton Sioux have been reported as occupying lands that include northeastern Wyoming. For this reason, the Teton Sioux are the only division that is detailed in the following sections, with exceptions given to tribal customs and beliefs generally shared by all three divisions.

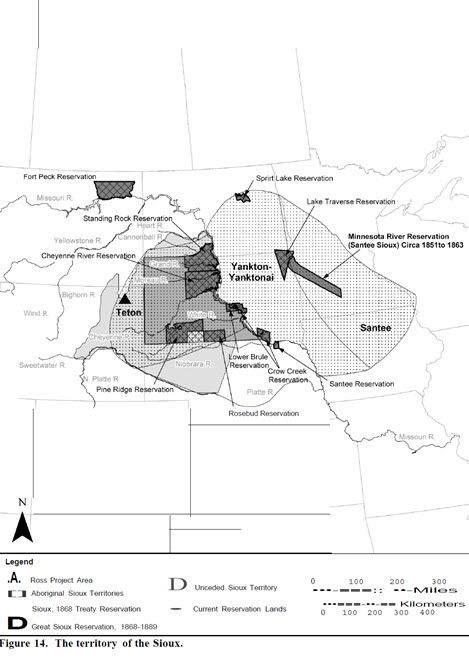

Early accounts of French explorers recorded the Sioux as occupying territories located east and west between the Missouri and Platte rivers, and divided the Sioux into the Sioux of the East, recognized later as the Santee, and the Sioux of the West, which contained all three of the Sioux divisions (Figure 14).  Gradual westward movement of Sioux groups has been documented as occurring between the mid-eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, largely due to pressure from other culture groups, such as the Chippewa and Cree, and from exploring new locations for hunting territories and new trade networks (DeMallie 2001). By the early nineteenth century, the Sioux occupied territories that were based on their division. The Santee migrated along the Minnesota River and its lower Minnesota extent; the Yankton/Yanktonai established territory east of the Missouri River region where they lived between the Minnesota and James Rivers; and the Teton occupied territories from the three forks of the Platte River to the forks of the Cheyenne River, including the Black Hills (DeMallie 2001). Although each Sioux division had established their own territory, the Sioux continued to hunt in each other’s hunting grounds and intermarriage between divisions was frequent (DeMallie 2001).

Gradual westward movement of Sioux groups has been documented as occurring between the mid-eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, largely due to pressure from other culture groups, such as the Chippewa and Cree, and from exploring new locations for hunting territories and new trade networks (DeMallie 2001). By the early nineteenth century, the Sioux occupied territories that were based on their division. The Santee migrated along the Minnesota River and its lower Minnesota extent; the Yankton/Yanktonai established territory east of the Missouri River region where they lived between the Minnesota and James Rivers; and the Teton occupied territories from the three forks of the Platte River to the forks of the Cheyenne River, including the Black Hills (DeMallie 2001). Although each Sioux division had established their own territory, the Sioux continued to hunt in each other’s hunting grounds and intermarriage between divisions was frequent (DeMallie 2001).

The Teton Sioux people have been recorded as being composed of seven bands: Oglala, Brulé, Blackfoot, Miniconjou, Sans Arc, Two Kettle, and Hunkpapa. An early account by the Lewis and Clark Expedition placed four bands of the Teton Sioux (Brulé, Oglala, Miniconjou, and possibly Yanktonai) on both sides of the Missouri River. The Brulé were located on both sides of the Missouri, White, and Teton Rivers; the Oglala on both sides of the Missouri River below the Cheyenne River; the Miniconjou band above the Cheyenne River and located on both sides of the Missouri River; and the Sans Arc located farther up and on both sides of the Missouri River (Ewers 1938). Territories for these specific bands were not always rigidly defined or absolute because all Sioux bands utilized these shared territories collectively for war, hunting, and trading (Ewers 1938).

According to Ewers (1938), Teton band regions were recorded as follows:

Brulé bands were located on the headwaters of the White and Niobrara rivers at the time of the report. Evidence of their location has been recorded as campsites that extended down toward these rivers, equally about half their length. Oglala bands were located at Ft. Laramie on the Platte and have been recorded as occupying territories that include the region northeast of the Black Hills, extending to the source of the Teton River and as far down as the fork of the Cheyenne River. They have also been recorded as occupying territories as far west as the Grand River. The Miniconjou bands were located from Cherry Creek on the Cheyenne River to Slender Butte on the Grand River. The Two Kettle bands were located along the Cheyenne and the Moreau rivers.

Ewers (1938) states that these bands seldom moved from north of the Cheyenne River and were highly mobile along both aforementioned rivers as well as the Grand River. The other bands, Hunkpapa, Blackfoot, and Sans Arc, were hard for outsiders to distinguish and were scarcely treated externally as separate bands. Early military journals (Talbot 1931 [1843]) also place some bands of the Teton Sioux, namely the Miniconjou, in Sweetwater Valley on a war party against the Crow. Accounts by Axelrod (1993) describe the Teton Sioux as utilizing the region located between the Black Hills and Powder River region by 1814.

Territories began to shift due to outside pressure during the early nineteenth centuries for all three Sioux divisions. The Teton Sioux are documented as attempting to abandon their nomadic ways and settle with the Arikara in an effort to escape this pressure and begin a horticultural lifestyle (DeMallie 2001). This effort was short-lived as tensions rose and divided the Oglala Sioux band in two (Tabeau 1939). The band later reconciled and abandoned horticulture. Meanwhile, Teton Sioux bands located to the south began to migrate west and further south toward the mouth of the White River (DeMallie 2001). Trade relations were established with the Arikara in later years as the Teton exchanged buffalo meat and robes for produce and winter encampment in the Black Hills (DeMallie 2001).

In the early to mid-nineteenth century, the Teton Sioux continued to ally themselves with the Cheyenne and Arapaho in an effort to drive the Kiowa and Crow from the Black Hills region (DeMallie 1980; White 1978). Other Sioux divisions shifted their focus toward the Missouri River (DeMallie 2001). This consistent pressure and conflict on the Plains and in the Powder River Basin led to intertribal warfare that was not uncommon among Plains tribes who had established territorial boundaries prior to European contact.

The U.S. government established territorial boundaries for each of the Sioux bands as well as other Plains tribes in response to increased conflict with European settlers and travelers. The historic signing of the Treaty of 1851 provided specific boundaries for the Teton Sioux, who had previously resisted “limiting tribal lands” (DeMallie 2001). In exchange for safe passage of European settlers as well as necessary approval to build roads, military posts, and secure emigrant trails, such as the Oregon/California/Mormon Trail system, the Sioux were granted the following lands:

Commencing the mouth of the White Earth River, on the Missouri River; thence in a southwesterly direction to the forks of the Platte River; thence up the north fork of the Platte River to a point known as the Red Butte, or where the road leaves the river; thence along the range of the mountains known as the Black Hills, to the head-waters of the Heart River; thence down Heart River to its mouth; and thence down the Missouri River to the place of beginning. (Ft. Laramie Treaty 1851)

Because of the growing number of breaches of the Fort Laramie Treaty by Euro-Americans, conflict between Plains tribes and settlers only increased. This was especially true along the Bozeman Trail, which various military units, such as Crook’s and Sawyers Expeditions, used as a primary corridor for enforcing the Treaty.

Because further conflict with the Plains tribes (especially the Sioux) followed the 1851 Fort Laramie Treaty, another treaty was drafted in 1868 that directly affected all three divisions of the Sioux and solidified their boundaries. This treaty established the Great Sioux Reservation, which included all of present-day South Dakota west of the Missouri River and areas north of Nebraska, north of the North Platte River, and eastern portions of Wyoming and Montana that extended to the summit of the Big Horn Mountains (DeMallie 2001). These boundaries also recognized hunting territories located on the North Platte and Republican Rivers, where buffalo was still sufficient in number (DeMallie 2001). As Indian agencies were established, many of the Teton bands such as the Oglala and Lower Brulé remained in unceded territory, located west and south of the Great Sioux Reservation.

The ‘Great Sioux Wars,’ between 1876 and 1877, were the result of consistent European contact and pressure. As a result, the Teton Sioux bands and Cheyenne joined forces and retaliated against gold miners, settlers, and other Native Americans who were friendly toward the U.S. government. During this war, the U.S. government sent cavalry troops onto the Great Plains to engage the tribes. The Great Sioux Wars resulted in several battles, most notably the Battle of the Little Big Horn, or at ‘Greasy Grass.’ There the combined Sioux and Cheyenne warriors overwhelmed the U.S. forces led by General Custer. By the end of 1877, attrition led the Sioux tribes and some Cheyenne bands to surrender to U.S. Cavalry troops at Fort Robinson in Nebraska (Brown 1970).

The primary Sioux homeland possessions are now limited to several reservations originally based on historic land divisions located in North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, and Montana. Modern-day reservations for all three divisions include the Cheyenne River Sioux, the Crow Creek Sioux, Fort Peck, Lake Traverse, Pine Ridge, Rosebud Sioux, Lower Brulé, Santee Sioux, Spirit Lake, and Standing Rock reservations. Bands of the Teton Sioux are located primarily on the Cheyenne River Sioux, Lower Brulé, Pine Ridge, Rosebud Sioux, and Standing Rock reservations.

Because of their access to prairie lands and their high mobility, the Teton Sioux relied heavily upon bison as their primary food source. The Sioux found every part of the animal either consumable or usable for utilitarian or decorative purposes (DeMallie 2001). Communal bison hunts in the summer were a major annual event for the Sioux. A typical hunt was supervised by the ‘hunt police’ who ensured that no one disrupted the hunt. Upon the signal of the hunt police, the hunters descended upon the bison herd for the kill. Butchering of the animals followed with some old men, women, and children arriving from the camp to help. All those who assisted in the hunt received a portion of the meat (DeMallie 2001). Once enough meat was processed, the tribe moved on. At this time, individuals were at liberty to supplement their food stores by hunting other animals such as elk, deer, antelope, and small game (DeMallie 2001).

The meat-rich diet of the Sioux was supplemented with a variety of fruits and vegetables (DeMallie 2001). Denig (1961) describes the prairie turnip, which he considered nearly inedible, as being relied on heavily by the Sioux during drought or other times of food scarcity, because this vegetable could be dried and stored for a considerable amount of time. The Sioux also foraged for wild artichokes, wild peas, red plumbs, various berries including chokecherries, and other tubers. Many of the fruits and vegetables were eaten fresh, but some amounts were also dried for use during the winter. Pemmican, a favorite food among the Sioux, was made by creating balls or patties from pounded dried meat, animal fat, and dried berries (DeMallie 2001). Numerous explorers also discuss the collection of wild plants for medicinal and ceremonial purposes (Denig 1961; Dunn 1886)

Several beliefs were fundamental to the Sioux religious worldview. One of these was the existence of White Buffalo Woman. It was through White Buffalo Woman that the Sioux acquired the Sacred Calf Pipe (Utley 1993). The Sacred Calf Pipe was thought to represent the entire cosmos of the Sioux and was essential to sanctifying relationships, vows, and predictions (Powers 1975). It also provided a powerful bond between the Sioux and the ‘Great Spirit.’

The Sioux also believed in Wakantanka, the ‘Great Spirit.’ Essentially, Wakantanka represented the power and mystery of the universe. In times of need, individuals could make appeals to Wakantanka for pity and in the process call upon the entire supernatural world for aid and guidance. Although any individual could ask for guidance from Wakantanka, only shaman could come close to understanding and utilizing the full power of Wakantanka (DeMallie 2001).

Another important belief among the Sioux was that of the earth as mother. The Sioux revered the earth as a powerful and sacred being and a provider of nourishment to all things. Certain geographical locations, specifically the larger area of Devils Tower, Inyan Kara Mountain, and other places in northeastern Wyoming—especially the Black Hills, were particularly regarded as being sacred (Dodge 1882; Sundstrom 1996; Vestal 1948). The Black Hills were and still are regarded as the “center of creation’s great hoop” and “the center of the world” (Pemberton 1985:293; Tallent 1899).

The Sioux had several sacred dances and ceremonies that required specific songs and rituals. Seven of these sacred dances were handed down by White Buffalo Woman and promoted the well-being of the entire tribe. Four of the seven sacred dances were conducted as part of their seasonal religious cycle. These dances included Dance for the Dead, the Scalp Dance, the Holy Dance, and the Sun Dance (Walker 1980). The Sun Dance, in particular, was a time for all Sioux bands to participate and come together to pray for an increase in the number of Sioux people and buffalo (DeMallie 2001). In the 1930s, Dick Stone interviewed several Sioux elders about the Sun Dances and other ceremonies that were held in northeastern Wyoming (Stone n.d.).

The Sioux maintained a system of chiefs that was primarily divided by territory. Sioux divisions were comprised primarily of small village bands that traveled independently of one another (Blair 1912) and consisted of five or six families that came together for spring gatherings and communal hunts in the summer (DeMallie 2001). Each Sioux division consisted of four chiefs who then appointed leaders that served as the police force, or the akicita, which changed yearly. This police force was established in all three Sioux divisions (DeMallie 2001).

The Sioux social system also was comprised of a series of men’s societies that controlled either policing or social duties. According to Sioux oral tradition, men’s societies were originally organized based on interpretations of a shaman’s dream (Hassrick 1964:149). One of these men’s societies included the Kit Fox Society, or the “Tokalas,” to which belonged men who had shown great bravery (Hassrick 1964:18). Many of these societies were age dependent and based on achievement. Other considerations included the family’s social and political status for the eligible person (DeMallie 2001).

Ideally marriage was preceded by a long courtship in which the bride was “purchased” through the complex exchange of gifts. Polygyny was commonly practiced, and the purchase of a woman often gave the man access to her sisters as appropriate marriage partners. The Sioux, having very strict taboos on inter-relations, were highly exogamous and, while there was no strict living pattern after marriage, the new couple generally lived patrilocally (DeMallie 2001).

The Sioux constructed fairly elaborate tipis that were made to enhance efficiency and allow for quick dismantling to suit their lifestyle as nomadic hunters and gatherers. Tipi construction usually required at least five bison hides to create a tipi at least eleven feet in diameter. Most tipis were decorated with quills, which were used to form “dangles made of short strips of rawhide wrapped with brightly colored porcupine quills to which were attached horsetails, feathers” (Hassrick 1964:211-212). Sioux campsites were often assembled around one large public tipi in the center of the camp for council meetings and ceremonies. The doors of all the tipis frequently faced the rising sun in the east. Visitors who entered the campsite were determined as friendly or hostile, depending on the direction from which they entered; from the east signified friend, from any other direction signified an enemy (Walker 1982:21-22).

Because they were highly mobile, Sioux cultural items are scarce. It is believed that the Sioux contained very few possessions as a result of this high mobility. Bows and arrows attributed to the Sioux were used for hunting. Tanned hides were acquired from big game hunts (DeMallie 2001). Other wild game was used by women to make clothing, which was decorated with geometric designs, and to make jewelry, such as earrings and necklaces: Historically, ear ornaments made of brass wire or dentalium shell were also used by women, as well as for other ornamental items produced for warriors (DeMallie 2001). Headdresses, war bonnets, and painted shirts were also created for ceremonies and other special occasions. Painted shirt designs often symbolized and distinguished leadership roles (DeMallie 2001).

The Sioux have been extensively documented in the Black Hills and northeastern Wyoming, a location where they identify their sacred hunting grounds as well as sacred grounds used to procure medicinal plants and perform sacred ceremonies (Dodge 1882; Dunn 1886; Niehardt 1953;Sundstrom 1996; Vestal 1948) ). In addition, Devils Tower is identified by the Sioux as the origin point for the Sacred Pipe (Boston Daily Globe 1911; Ford 1954; Looking Horse 1987; Stone n.d.).

TRIBAL RESOURCES

Lower Brule Sioux Tribe

187 Oyate Circle

Lower Brule, SD 57548

605.473.5561

Oglala Lakota Nation

PO Box 2070

107 West Main Street

Pine Ridge, SD 57770

605.867.5821

Rosebud Sioux Tribe

2413 Legion Ave

Rosebud, South Dakota 57570

605.747.2381

Santee Sioux Nation

108 Spirit Lake Ave. W

Niobrara, NE 68760

402.857.2772

Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community of Minnesota

2330 Sioux Trail N.W.

Prior Lake, MN 55372

952.445.8900

Standing Rock Sioux Tribe

Bldg. #1 N Standing Rock Ave.

Fort Yates, ND 58538

701.854.8500

Upper Sioux Community, Minnesota

5722 Travers Lane

P.O. Box 147

Granite Falls, MN 56241-0147

320.564.2360