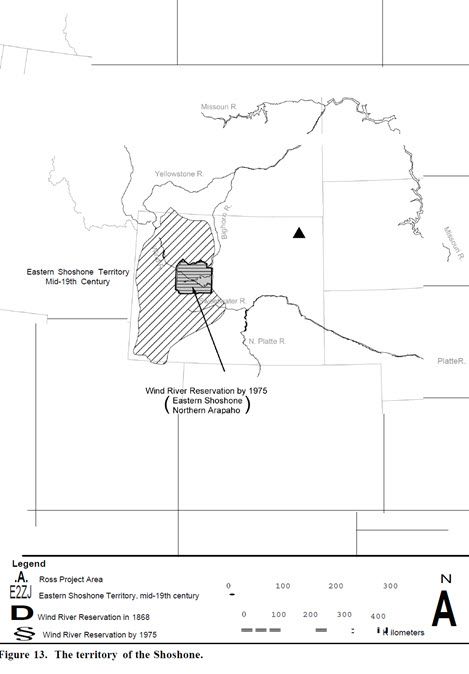

The Shoshone are linguistically and culturally related to other tribes of the Great Basin cultural region such as the Comanche, Ute, Paiute, Bannock, and others (Murphy and Murphy 1986). The Shoshone fall into approximately three groups: Western Shoshone, Northern Shoshone and Bannock, and the Eastern Shoshone. It should be noted that because Shoshone culture is marked by a fluid and changeable social organization, the division of these three groups has been based primarily on location (Murphy and Murphy 1986). The Shoshone moved on to the Great Plains from the Great Basin in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries (Shimkin 1947) (Figure 13). Within the current context that the Eastern Shoshone are the only Shoshone culture group detailed.

Shimkin (1986) divided the Eastern Shoshone into two groups: the “Buffalo Eaters,” the kuccuntikka, who also were known as the “Sage Brush People,” and the “Mountain Sheep Eaters,” the tukkutikka. The “Buffalo Eaters” centered themselves in the Green and Wind River valleys but migrated over the entire territory known to them as Eastern Shoshone territories. The “Mountain Sheep Eaters” inhabited the central Rocky Mountain area, including the vicinity of Yellowstone Lake. Shimkin (1947) has argued that the Eastern Shoshone should be classified as a Northern Plains tribe rather than a Great Basin tribe. The Eastern Shoshone are thought to be the first tribe of the Northern Plains to receive horses from the Comanche and Ute. They are also thought to be the main supplier of horses to the Nez Perce and Crow (Lavender 1992).

Once mounted on horseback, by the mid-1700s, the Eastern Shoshone controlled a huge range extending outward to Saskatchewan and South Dakota, influenced by buffalo hunting and through trade with various Plains tribes and other Shoshonean groups. According to Steward (1937), Shoshone territory “extended from the region of Little Lake and Death Valley in California, northward across most of the eastern half of Nevada into northern Utah, southern and eastern Idaho, a little of adjoining Montana and western Wyoming.” Murphy and Murphy (1986) describe their range as follows:

The Eastern Shoshone of Wyoming conducted most of their buffalo hunting in the region beyond South Pass, into the valleys of the Wind and Big Horn rivers. Their winter camping grounds were generally in the area of the Green River. During the spring and summer small parties sought subsistence in the mountains of northern Utah and southwestern Idaho, and their routes often took them through the same country traveled by similar small groups of Snake River people.

Shimkin (1947) also identifies Shoshone territory as consisting of the western half of the Big Horn Basin, Owl Creek Mountains and the adjacent plains, the Powder River Valley, the lower drainage of the Sweetwater and the upper North Platte rivers, the Red Desert, the hill country between Fort Bridger and the Great Salt Lake, and the inter-mountain country surrounding Jackson Hole. Unlike the Western Shoshone and Northern Shoshone and Bannock, the Eastern Shoshone were thought to have formed larger, highly militaristic groups or bands (Shimkin 1986) because of their greater dependence on buffalo and more frequent contact with other Plains tribes.

Shimkin (1947) also identifies Shoshone territory as consisting of the western half of the Big Horn Basin, Owl Creek Mountains and the adjacent plains, the Powder River Valley, the lower drainage of the Sweetwater and the upper North Platte rivers, the Red Desert, the hill country between Fort Bridger and the Great Salt Lake, and the inter-mountain country surrounding Jackson Hole. Unlike the Western Shoshone and Northern Shoshone and Bannock, the Eastern Shoshone were thought to have formed larger, highly militaristic groups or bands (Shimkin 1986) because of their greater dependence on buffalo and more frequent contact with other Plains tribes.

Not all contacts with neighboring tribes were peaceful or beneficial to the Shoshone. In fact, during the eighteenth century, the eastern range of the Shoshone was greatly reduced by increasing conflicts with the Arapaho, Teton Sioux, and Cheyenne. As a result of these conflicts, the Eastern Shoshone withdrew from their eastern ranges. By the time they encountered Lewis and Clark in 1803, the Eastern Shoshone were living along the western slope of the Rocky Mountains in Montana, Wyoming, and Colorado (Stamm 1999). Of the Plains tribes living in Montana and eastern Wyoming, the Flathead were the Shoshone’s strongest allies, with whom they traded, socialized, and intermarried (Stamm 1999).

Frequent contact with other Plains tribes, both hostile and friendly, also led to their interaction and friendly relations with white traders and settlers and government agents (Forney 1858; Mann 1862; Dodge 1905; Hebard Collection 1930). This is evidenced by Washakie’s offer of Eastern Shoshone services to the U.S. government’s campaign against the “hostile” Indians, such as the Sioux, Arapaho, and Cheyenne, as well as small numbers of Kiowa occupying areas along the North Platte River in 1865. One account is documented in 1926 by Jeannette Easton in the Grace Hebard Collection (1930), in which she shares her childhood memories of her father’s stories concerning the Shoshone/white relations:

As a child I heard them say many times, when the indians [sic] were bad on the trails, ‘If we can only make Washakie’s camp we are safe.’ Once… some of our boys were freighting, the heavy snows and bad roads… had reduced them almost to starvation… in a pitiful condition [and] harassed by Indians. Washakie’s braves… sent (word) to the chief that white men were being pursued. He lost no time in coming to their rescue, keeping [them] for days… showing every courtesy in his power.

In June 1858, attempts were made to provide a reservation for the Shoshone, in particular to Chief Washakie’s band (Shimkin 1986). No reservation was established until 1862 (Forney 1858). During the interim, the Shoshone and Bannock escalated their raids and ambushes on a number of mail and stage coach companies traveling south through Wyoming to Salt Lake City, along the Oregon Trail, and at Fort Bridger (Hebard Collection 1930:106). In April 1862, 100 men from the Nauvoo Legion were sent to the area around Independence Rock for 90 days, but they did not encounter any tribes (Hebard Collection 1930). It was believed that the Shoshone and Bannock had moved their families to the Salmon River Country out of the range of the soldiers (Hebard Collection 1930). Documented accounts, however, showed that Washakie, by then the main chief of the Shoshones, had disavowed “any acts of violence or theft” (Mann 1862). Subsequently it was recommended that Washakie’s band be provided a reservation either in the Wind River Valley, the Valley of Smith’s Fork River, or in the region around the divide between of the Henrys Fork and the Green River drainages. This agreement ultimately was derailed, however, due to the treaty agreement the U.S. made with the Crow Tribe (Hebard Collection 1930).

In 1863 the Fort Bridger Treaty was signed, designating a territorial boundary for all Shoshone that reflected their traditional base from the early 1800s (Hebard Collection 1930). In response to a number of failures on the part of the federal government to meet its obligations under the treaty, Washakie informed the Utah Superintendent that his band would have to hunt near Fort Bridger and that they now depended upon “their Great Father to help them to live now that the white men whom he would not fight had driven off his game” (U.S. Serial Set Number 4015, 56th Congress, 1st Session:786; Hebard Collection 1930). By September 1865, Washakie’s band had increased in population with much of the increase coming from an influx of other Shoshone bands including the Bannock, and the Northern and Eastern Shoshone.

In 1866, Superintendent Head enlisted Washakie as an advisor to assist in keeping the Bozeman Trail open. The trail cut directly through Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho treaty territories in Powder River country (Hebard Collection 1930). This trail allowed passage to Montana mines, and also disrupted big game hunts for tribes with hunting grounds already established within the Powder River Basin. Efforts were made by Washakie to communicate the concerns of the various tribes for their established hunting territories and reserves, stating that the Powder River Basin “had always been claimed by the four principal tribes—the Sioux, the Cheyennes, the Arapahos and the Crows” (Hebard Collection 1930). Washakie further explained that these tribes saw the Bozeman Trail as an effort on the part of the white man to starve them and deny them their hunting grounds (Hebard Collection 1930).

In 1868, the Eastern Shoshone and Bannock assembled at Fort Bridger for a “council” regarding the territory issue. Washakie was originally interested in the country from the highest point of the Uintah Mountains (south of the southwest border of present day Wyoming into Utah), Wind River valley and the Salt Lake City meridian to the line of the North Platte River to the mouth of the Sweetwater River (Hebard Collection 1930). At the government’s insistence, however, Washakie relinquished claims on the Green River Valley due to the construction of the Union Pacific Railroad. Thus, the original Wind River Reservation was established. In 1878, The Northern Arapaho Tribe relocated to the Wind River Reservation where the two tribes reside today. The original reservation land area of approximately 44.5 million acres went through several reduction phases. First, with the Brunot Land Cession in 1874, then two other land cessions in 1896 and 1904 that further reduced their land base to one-fifth of its original dimensions (Hebard Collection 1930). In the 1940s, much of the acreage that had been lost during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century was returned to the tribe. The current boundaries of the reservation are close to those originally established in 1868 (Kappler 1979).

In the period 1842-1875… the bands would gather each spring in Wind River Valley… they would descend the Big Sandy, crossing it near the Lombard Ferry… They would go… to Fort Bridger [to] stay for the summer. Early in the fall, they would return to Wind River and separate for the bison hunt. The band led by Ta’wunasia would go down the Sweetwater to the upper North Platte. That led by Di’kandimp went straight east to the Powder River Valley. (Shimkin 1947:247)

Additional accounts of subsistence have been detailed in Wilson (1910) that include fishing and hunting practices, as well as poultice applications, surgeries, and the use of salt water and skunk oil in the treatment of injuries and illness (Wilson 1910). Other types of subsistence, such as plant gathering, included some berries, seeds, and roots gathered during the late summer and fall months (Shimkin 1986). Favored plants included currants, rose berries, hawthorns, gooseberries, wild roots, wild onion, camas roots, honey plants, gilia, cinquefoil, and the seeds of thistles and sunflowers (Shimkin 1947, 1986).

The Eastern Shoshone practiced two forms of religious belief: one that was achieved on a personal level that was guided by personal success through the use of supernatural powers, and another that could be directed toward the community and used in certain ceremonies, such as the Father Dance, the Ghost Dance, and the Sun Dance (Hultkrantz 1986; Shimkin 1986). Generally, the Shoshone believed that they obtained their powers through dreams and visions and they received these dreams by communicating with spirits who lived in certain caves and rock outcroppings containing pictographs (Malouf 1974; Shimkin 1986; Steward 1943).

Shimkin (1986) notes that the use of supernatural beings created from nature and the power they contain, known as poha, were central to the shaman, pohakani, “the one who has power.” The relationship between the shaman and this power was complimentary, being supplemental and dependent upon one another. Both poha and pohakani could be expressed through the use of ceremonial dance and vision quests (Shimkin 1986).

As documented by Voget (1984:168), the Crow Chief Yellow Hand introduced the Sun Dance to the Shoshone. The dance was identified by Voget as an adaptation of the Crow Beaver Dance and connected to the sacred tobacco of Crow cosmology. Shimkin (1953:409, 413) challenges this point, however, and maintains that the Shoshone derived their Sun Dance from the Kiowa, stating “it appears that the Shoshone derived their Sun Dance from the Kiowa via the Comanche, with subsequent strong influence from the Arapaho and lesser influences from the Blackfoot or Crow” (Shimkin 1953). In either case, the Eastern Shoshone adaptation of the Sun Dance, much like those of other tribes in the Great Plains region, was initiated during the winter and took place in late spring or early summer (Shimkin 1953). Other ceremonies integral to the Eastern Shoshone included the adaptation of Peyote Ceremony in the late nineteenth century, and the incorporation of Peyote use into the Shoshone Sun Dance by this time (Voget 1984). A more detailed description of the Peyote ceremony may be found in Stenberg (1946).

Vision Quests involved sleeping at sacred sites located near pictographs, also known as poha kahn or “house of power,” or at Shaman graves (Shimkin 1953). Many of these vision quest sites have been identified near Dinwoody Canyon on the Wind River reservation, which is said to contain rock art panels containing pictographs of Water Ghost and Rock Ghost beings (Gebhard and Cahn 1950).

Little has been documented regarding places of traditional cultural importance to the Eastern Shoshone. They do not speak freely of these particular sites (Shimkin 1938). However, the few areas or sites of traditional cultural importance that have been recorded include land features, dance grounds, trails, petroglyph sites, places where spirits live, burial sites and rock art sites, all of which are especially culturally sensitive. Many sites, such as the Bighorn Medicine Wheel in Wyoming, have been regarded as culturally important to many Plains tribes. Bull Lake, located on the Wind River Reservation, also is considered a place of traditional cultural importance. They regard this area as the “home of monsters” and it is said to be “the place where ghost people play the hand game” (Shimkin 1986). The Shoshone view Devils Tower to be sacred not only to them, but to Native Americans in general. The Shoshone do not provide many details regarding their specific views, however at least one ethnographic account indicates that the Shoshone share similar beliefs to other groups associating the formation with the Bear Spirit (Hanson and Chirinos 1997).

Although by the time Lewis and Clark first encountered the Shoshone, when the tribe had withdrawn westward from regular settlement on the Plains, the organization of the tribe resembled that of other Plains groups in the region (Stamm 1999). During historic times, the Eastern Shoshone would disperse into three to five bands that would congregate in the winter or early spring. Each of these bands had a loose association with territories located in western Wyoming and were organized around one chief who controlled and was aided by two militaristic societies, the Yellow Brows and the Logs, and their assistants (Shimkin 1986). The two military societies were complementary to one another. The Yellow Brows usually were comprised of young men who ordered tribal marches or collective hunts and were “committed to fearlessness” (Shimkin 1986) while the Logs were comprised mainly of middle-aged men who “acted as rear guards for the Yellow Brows and were highly honored for military deeds” (Shimkin 1986).

Age and gender also played an important role in Shoshone society. A woman’s status was highly dependant upon her husband’s role in band and society. Men moved up in rank as they acquired supernatural power; as the husband rose in rank so did his wife (Shimkin 1986). However, Johnson (1975) notes that women played a key role in the formation of alliances between the tribe and white and Métis trappers and traders.

Originating in the Great Basin, the Shoshone developed traditions of pottery and basketry. However, the Eastern Shoshone adapted to Northern Plains subsistence more so than the other Shoshone divisions. Eastern Shoshone adopted mobile residences and constructed tipis, consisting of at least ten buffalo hides and twelve long and twenty short poles, covered in buffalo hide (Shimkin 1986).

Decorative work of the Eastern Shoshone shares similarities to that of other tribes with whom they had contact. By the late 1880s, Stenberg (1946) documents that the Eastern Shoshone adopted many of the floral patterns from the Crow and incorporated them into their motifs. Similarly, Shoshone representations of stars and feathers in their beadwork are similar to those of the Arapaho (Stenberg 1946).

Various researchers have reported that Shoshone territories traditionally extended as far east as the Powder River. It is difficult to ascertain, however, the extent of Shoshone land use in Northeastern Wyoming. Ethnographic accounts suggesting that they recognized the importance of Devils Tower infer that they made use of the areas as far east as the Little Missouri and Belle Fourche Rivers. In general, the Shoshone prefer to retain knowledge they may have among themselves. See Figure 13 for the historic territories occupied by the Shoshone; note that these may not include all areas used by them.