Kiowa

The Kiowa speak a language that is related to the Tanoan-Kiowan linguistic group that is often associated with the Tanoan language spoken by several Puebloan groups of the Southwest. This suggests that the Kiowa may have early origins in the southwest. However, many scholars believe the Tanoan-speaking people broke into separate groups while still in the north and most moved further south, while the ancestral Kiowa stayed in the western Montana region (Levy 2001). It is believed that at one time, several different dialects of Kiowan may have been spoken by different groups, however, by the time of early contact with Europeans, only one identifiable dialect was recognized (Goddard 2001).

Kiowa-Apache

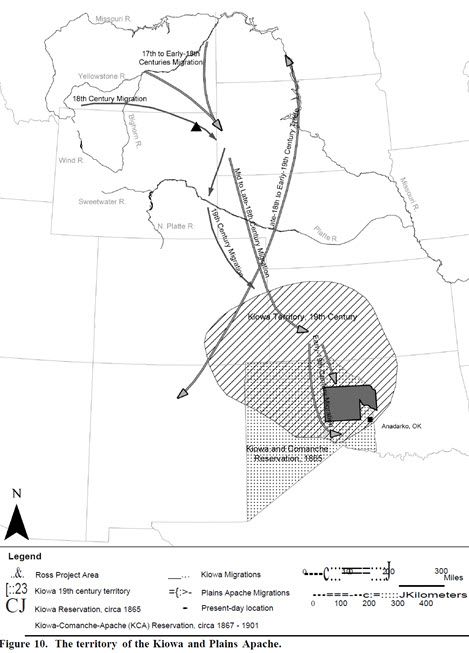

The Kiowa-Apache speak a Southern Athapaskan dialect related to the Jicarilla and Lipan Apache groups of northern New Mexico and Texas. It is thought that the Kiowa-Apache were part of a large group of Apache tribes known historically as the Plains Apache. This name is a term used to group all Apache tribes that lived between the Black Hills in South Dakota and the Canadian River in Northern Texas (Foster and McCollough 2002) (Figure 10). The Kiowa- Apache later were given the name Plains Apache mainly to differentiate them from groups that later moved out of the Central Plains into different regions.

Documented accounts of when these Apache joined with the Kiowa are unknown. Previous research has indicated that the Kiowa-Apache cannot remember a time when they were not joined with the Kiowa (McAllister 1949:1). Yet, many scholars disagree and believe the Kiowa- Apache differ both linguistically and culturally (Brant 1949; Newcomb 1970; Bittle 1971). Because of this, both groups have been separated by subsection in the following section only.

Kiowa

Kiowa oral tradition states that the tribe originated in an arctic region living in “ice” houses (Tsonetokoy 2002) and moved to the headwaters of the Yellowstone and Missouri rivers in Montana. Oral tradition also states that a dispute between band chiefs over an antelope udder caused a split in the tribe. It is believed that the winning group moved northwest and disappeared, while the losing group moved southeast and became the Kiowa. The Kiowa moved southeast from Montana into the Black Hills and Devils Tower areas (Sundstrom 1996). This relocation brought them very close to the Crow tribe, who, it is thought, provided them with their first horses and hunted bison with them (Tsonetokoy 2002; Sundstrom 1996:2f-3, 2f-6). The Kiowa lived in the Black Hills for some time trading extensively with the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara. Spanish sources place the Kiowa in the Great Plains region in 1732, and it is believed they were a horse-mounted tribe by 1725. Kiowa oral tradition includes several narratives describing eastern Wyoming’s Pumpkin Buttes, Big Horn Mountains, and Badland regions (Harrington 1939:174-176; Sundstrom 1996:3c-5, 3c-7; Tsonetokoy 2002).

This relocation brought them very close to the Crow tribe, who, it is thought, provided them with their first horses and hunted bison with them (Tsonetokoy 2002; Sundstrom 1996:2f-3, 2f-6). The Kiowa lived in the Black Hills for some time trading extensively with the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara. Spanish sources place the Kiowa in the Great Plains region in 1732, and it is believed they were a horse-mounted tribe by 1725. Kiowa oral tradition includes several narratives describing eastern Wyoming’s Pumpkin Buttes, Big Horn Mountains, and Badland regions (Harrington 1939:174-176; Sundstrom 1996:3c-5, 3c-7; Tsonetokoy 2002).

The westward pressure of the Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho tribes in the Black Hills region in the late eighteenth century forced the Kiowa to move south (McCready 1998). The Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1805 was told that the Kiowa lived along the North Platte River in southeastern Wyoming. This southern move put the Kiowa into conflict with the Comanche who themselves were being pushed further south. Hostilities between the Comanche and Kiowa continued as the Cheyenne and Arapaho pushed the Kiowa even further south. The Kiowa and Comanche made an alliance against the northern tribes in 1806 that allowed the Kiowa to move to the south bank of the Arkansas River (Mayhall 2002). The Kiowa began to concentrate their raiding into Mexico and Northern New Mexico, taking slaves and horses. In 1840 the Kiowa made peace with their northern and eastern neighbors making nearly all of the tribe’s territory secure (Levy 2001). The Kiowa were known to avoid direct conflict with Euro-Americans and the U.S. government. Wishing to avoid reprisals from the U.S. military, the Kiowa in 1834 established friendly relations with the Creek and Osage tribes, who also had good relations with the U.S. The Kiowa signed formal treaties with the U.S. government in 1837 (Kappler 1904- 1941). The Treaty of Fort Atkinson in 1853 formed a peace with the U.S. and Mexico and allowed for the construction of roads and military posts within the tribe’s territory. However, the Kiowa continued to raid into Texas, northern Mexico, and New Mexico. In 1864 a Kiowa village was attacked and burned by the U.S. military (Pettis 1908). The attack sparked a period of hostility between the tribe and the military, leading to the Little Arkansas Treaty of 1865, which sought to stop hostilities, and ultimately led to the tribe moving to a reservation shared with the Comanche in western Oklahoma and Texas.

Kiowa-Apache (Plains Apache)

Although the Kiowa-Apache closely relate themselves to the Kiowa, the Kiowa-Apache language, social structure, beliefs, customs, and some folklore are considered distinctly Athapaskan (Brant 1949). Athapaskan migrations south from northern Canada are believed to have occurred around the 1500s. It is believed that these Plains Apache groups may have settled all throughout the Central Plains region. Based on seventeenth century accounts of Robert de LaSalle, Hodge (1912) surmises that the Kiowa-Apache ranged to the south of the Platte River, trading a far south as New Mexico—where they traded with the Spanish for horses. Originally a more centralized tribe, it is believed that the Kiowa-Apache were scattered on to the western portion of the Southern Plains by the Comanche in the eighteenth century (Foster and McCollough 2001) (Figure 10). Foster and McCollough (2001) state that, of the Plains Apache, bands of the Jicarilla fled into modern-day New Mexico to seek protection with the Spanish, while the Lipan band moved to southern Texas. The ancestral Kiowa-Apache band instead relocated into the Black Hills of South Dakota and Eastern Wyoming. In 1805, Lewis and Clark describe the territory of the Kiowa-Apache as between the two forks of the Cheyenne River (Hodge 1912). The Kiowa-Apache became allies with the Kiowa for protection, and quickly became integral members of the Kiowa tribe (Foster and McCollough 2001). No historical account of when the Kiowa were adjoined with the Kiowa-Apache is available, but most historical scholars believe the two tribes merged around 1700 (McAllister 1949). The Kiowa themselves claim that they do not remember a time when the Kiowa-Apache were not part of the tribe.

The Kiowa along with their Comanche allies, moved to a reservation in 1865. At their own request, the Kiowa-Apache did not initially join the Kiowa and instead joined the Cheyenne and Arapaho. By 1867, most of the Kiowa-Apache had rejoined the Kiowa who had moved onto a reservation with the Comanche although some of the Kiowa Apache continued to live with the Cheyenne and Arapaho until 1875 (Hodge 1912; Swanton 1952). The Kiowa reservation covered the northern portion of Texas and the Panhandle and western third of Oklahoma. Under the U.S. policy of allotment in severalty, the reservation was later divided up into 160-acre allotments with the excess being sold by the U.S. government for $1.25 per acre (Levy 2001). The Kiowa-Comanche-Apache reservation, as it came to be called (or the KCA) was divided into common pasturelands and homesteads for white settlers and ranchers. The tribal connections began to break apart as the tribe’s territory shrank further and further. Later efforts by the tribes to work together and form common business interests has resulted in the tribes being physically separated in the small areas of tribal land with the area of the original reservation but connected under a single tribal authority based in Anadarko, Oklahoma. When the Kiowa were assigned a reservation in 1867, the Kiowa-Apache requested to be located with them. The Kiowa-Apache also were assigned their own small reservation in Oklahoma, but are connected to the tribal government in Anadarko as well (Foster and McCollough 2002).

The Kiowa were primarily bison hunters who were likely involved in bison jumps and pounds in the prehistoric periods before the introduction of the horse. However, no prehistoric sites have been clearly associated with the Kiowa in the region of northeast Wyoming. The Kiowa relied on dog-drawn travois for transportation until the introduction of the horse in the early 1700s (Mayhall 1962). The Crow are believed to have introduced the horse culture to the Kiowa. The Crow provided the first horses and taught the Kiowa to hunt bison from horseback (Levy 2001:907). The Kiowa continued to hunt other game such as antelope, elk, and deer. Tribal mobility and subsistence activities were all based around the seasonal bison hunts. Winter seasons were spent in large camps near watercourses for access to firewood and shelter, with small bands breaking away to hunt the scattered bison herds. In late spring when the bison began to gather into large herds to migrate north so did the Kiowa. The tribe would gather together into a few very large bands. In summer related bands would gather for communal hunts, raid planning, and ceremonies. Kiowa women also provided a stable food source by gathering plants and roots, including chokecherries, plums, grapes, blackberries, wild onions, and prairie turnips (Jordan 1965).

In the Kiowa belief system, all natural things hold a spirit force called dwdw, or “sacred power.” “Sacred Power” is a pervasive force that is localized in certain spirits, animals, or places. Eagles or buffalo, as well as the sun, moon, and winds, were considered important personifications or concentrations of power (Levy 2001). Supernatural power is not equal in all things and some things can have more “power” than others. For example, ‘powers from above’ have stronger dwdw than earthly animals; and the Sun has stronger dwdw than the Eagle, which is stronger than the buffalo, etc. (Kracht 1997). The dwdw is not inherently good or evil; it is the person requesting spiritual help who decides how to use it, however a “source” of dwdw can judge the seeker to be deserving of its help (Levy 2001). Landscapes and certain land possess the dwdw; these places of power can be places of personal spiritual connection, such as fasting sites. In earlier times, only those in the social rank of Kiowa society, the ode, were able to solicit dwdw. Those in lower social ranks had to pay for this power and could only receive dwdw by learning from one who already possessed this power. Vision quests usually took place in seclusion at the highest point possible, such as a mountaintop, for four nights. Persons on the vision quest fasted, smoked, and prayed. They prayed for three nights and on the fourth night, the person returned home. If successful, a vision of a spirit appeared who would become a guardian or helper. It was thought that a man could not succeed in life without a spirit helper (Levy 2001). Vision quest seekers sought power for war or healing which led to greater prestige and potentially higher rank among the tribe (Kracht 1997).

The Kiowa also kept several medicine bundles. The bundles were provided by a mythical hero who transformed himself into ten medicine bundles for the tribe to use and pray to. The bundles played an important part in Kiowa society as each bundle had specific curing and social powers and helped to keep the tribe peaceful. Each of the ten bundles was kept in a separate lodge, and since the bundles had taboos against any violence in their presence, the lodges were considered refuges where disputes would be settled (Levy 2001).

The most important religious ceremony of the Kiowa was the Sun Dance. The Sun Dance was held annually while Kiowa bands joined together in the summer months to hunt bison and pray for successful hunts. Participants sought to gain supernatural power or increase the amount they already had. The central aspect to the Kiowa Sun Dance ceremony was the Taime, a small image representing a human figure. The Taime was prayed to and provided gifts to ensure large bison herds and secure good health for the Kiowa (Levy 2001). Two Taime bundles were in the Kiowa’s possession in the late 1770s, one male and one female. The two Taime were acquired by the Kiowa from an Arapaho man who married a Kiowa woman, this man is said to have received the bundles from the Crow. It is also thought that the Kiowa were practicing the Sun Dance ceremony before they received the Taime bundles, but coincidentally it [is] also thought that the Crow taught the ceremony to the Kiowa. Unlike other Plains tribes, the Kiowa did not partake in the self-mutilation or piercing. The Kiowa believed that any blood spilled during the Sun Dance would spoil its power and doom the tribe (Mooney 1898).

The Kiowa also had a network of men’s Shield Societies that could disperse dwdw to relatives, friends, or allies. A person who had acquired dwdw could make shields depicting his power and pass it and its associated abilities to an heir or sell it to a friend. There were four prominent shield societies: the Taime, Eagle, Buffalo, and Owl. The Taime were considered the oldest shield society and were associated with the protection of the Taime bundles and the Sun Dance Ceremony. The Eagle Shield society was associated with power in battle. The Buffalo Shield Society was created by a woman, but only her male descendants could be members. This society had powerful healing gifts and [members] often acted as medics during battles. The Owl society had the power to prophesy, enlist the help of the dead and to find lost items. These male societies held a great deal of political and religious power within the tribe. The most notable women’s society was Bear Old Woman Society. The Bear Old Woman Society had only female members but was considered closely related to the Taime and other shield societies. These women wielded considerable power and were feared by members of all other societies. The Bear Old Woman Society members acted like bears, wore bear claw necklaces, and sometimes dressed like men (Marriott 1968). The parents of sick children would promise a feast to the society during a Sun Dance ceremony to ask for their help in healing the child (Parsons 1929). Bear power was considered more powerful than the Taime or Medicine bundles. They were so powerful that young people and children were removed from camp when a Bear Old Woman meeting was taking place. This society was considered the oldest religious society of the tribe (Levy 2001).

During the early reservation period several new Kiowa religious ceremonies emerged as a result of contact with European culture and dealing with the U.S. Government. The Ghost Dance and later the Peyote Ritual were both practiced extensively by the Kiowa and Kiowa-Apache. The combination of several military defeats in the 1870s and the restriction of their nomadic lifestyle encouraged Kiowa warriors to find a new source of power in the Ghost Dance (Levy 2001). The purpose of the Ghost Dance ceremony was to bring back the conditions of the past, such as large bison herds, the absence of white people, and freedom to roam. The other ceremony that started at a similar time as the Ghost Dance was the Peyote Ceremony. This ceremony was adopted from the Mescalero Apache and flourished on the Kiowa-Comanche-Apache reservation in Oklahoma. The ceremony incorporated the use of peyote cactus buds as a hallucinogen. The ceremony may have appeared as early as 1870, but did not become widely popular until the late 1890–1900s Reservation Period. It has been argued that the source for the use of the Peyote Ceremony by other Native Americans can be traced to the Kiowa-Comanche-Apache (KCA) Reservation during that period (Darnell 2001). This period also saw the early development of the powwow gatherings where members of several tribes came together. It is through the powwow gatherings that the Peyote ceremonies spread throughout the Indian communities of North America (Phillips et al. 2006:93-95).

The Kiowa and the Kiowa-Apache both held sacred views towards Devils Tower, located west of the Project area. While many of the tribes referred to the formation as something that translates to “Bear Lodge,” the Kiowa term for the formation T’sou’a’e means “aloft on a rock”. Nevertheless, the story regarding its creation remains similar, with the formation rising out of the ground to protect a woman from her sibling who had turned into a bear (Sundstrom1996).

The Kiowa followed a bifurcate merging kinship system, where all children of the same generation were called by the same term. A man’s brother’s children were called by one term and his sister’s children were called by another term. This bifurcation could be broken down to the nuclear family level, which consisted of a married couple and their non-married children (Levy 2001).

A single band of Kiowa would have 10 to 20 families in the group. A prominent wealthy man led a band comprised of his son’s-in-laws and their families, poorer relatives, and individuals with no family ties. The size of a band varied considerably based on the prestige of the leader and the season. The leader was responsible for maintaining order in the band without using physical violence, directing the movements of the band and, organizing the defense of the camp. There were about 40 Kiowa bands that consisted of 35 or more people each. Kiowa tradition states that these bands were grouped together into seven autonomous divisions each made up of several bands. These divisions included the Biters or Arikara, this name comes from the close trade relations this division kept with the Arikara tribe; Elks who are considered to be the Kiowa proper, and the original division of the tribe; the Big Shields; Thieves; Kiowa-Apache; Black Boys, who were considered the smallest division; and the Pulling Up division who are said to have been eliminated by the Sioux in the 1780s (Mooney 1898; Levy 2001).

Kiowa society recognized status based on social rank and involvement in military societies and honor gained in battle. Although not permanent, status was based on individual prowess and achievements, and could be lost or gained (Meadows 1999). Meadows (1999:43-44) documented four levels of social rank:

The ode or odeogop were affluent, had war honors, were generous, courteous, the headsmen of the tribe, etc. The aude were the favored and usually oldest male or female children of an ode family, received the best clothes, food, and often their own tipi, and were not required to work as youths. The odegufa were the second best, largely the same as ogop except lacking in war honors and thereby being less wealthy; they included many specialists in religion, doctoring, art, and upcoming war leaders. The kauaun (pitiable) were common people, hardworking but poor, including many captives. The daufo (no good, worthless) were a very small minority of unmotivated, lazy, and dishonest individuals.

These social ranks were not rigid, however, and a person could exercise a great deal of social mobility by gaining prestige and wealth and moving up the ranks or losing it and moving down. Everyone had the opportunity to improve his or her rank, though those born to the lower ranks had more obstacles to overcome in achieving a higher rank. A middle ranked man, for instance, would have to win battle honors to gain enough prestige and supernatural power to advance in the ranks. Women were given the social rank they were born into but could marry into another rank. Mexican women captives, often part of the second lowest social rank, were often married into the highest two social ranks illustrating the amount of social mobility a woman could hope to achieve in the tribe.

Once the Kiowa acquired the horse, the animals played an integral role in the development of status of an individual. The increased mobility of the horse led to increased raiding of other tribes, made possible new ways to demonstrate one’s bravery and facility as a horseman, and made it possible to acquire more possessions (Levy 2001).

The wealth and opportunity differences between the groups could have led to many disputes, but the Kiowa culture itself made up for these disparities. First, men of the highest two ranks were expected to be very generous, dignified, and gentle towards women. Not being so would cause a man to lose a great deal of prestige and respect very quickly. Second, the Kiowa had several men’s societies in which membership crossed all family and rank associations. All men were part of some society that opened up social connections to other bands and other ranks. In addition society members were obligated to help their society brothers in times of hardship (Levy 2001). There were several men’s societies that were quasi-egalitarian, but the responsibilities and wealth required to become a member tended to filter out those from the lower ranks.

Some examples of the more prominent societies included the ‘Horses’ which was a low ranking society of young men from all classes; the ‘Black Legs’ who were one of two societies that required battle honors as a prerequisite for membership; the ‘Skunk Berry People’ (also known as the Gourd Dancers) who were considered the most influential and the oldest society; and the ‘Principle Dogs’ which was a highly exclusive society that had at most ten full members, all of whom had to be from the higher ranks and have extensive battle honors. The Principle Dogs were the most elite tribal leaders and the membership requirements made it impossible for anyone but the most affluent and prestigious to join. A women’s society known as the ‘Calf Old Women’ held a great deal influence in the tribe and was regarded as being equal in stature to many of the men’s societies. The Calf Old Women society held war power and was honored with feasts by warriors upon their departure to battle and their return camp. All the societies were responsible for keeping order within their membership and organizing religious ceremonies like the Sun Dance (Levy 2001).

Prior to European contact, the Kiowa and Kiowa-Apache lived in tipis that varied in size. Large tipis were about 20 feet in diameter. Tipi doors almost always faced east. The Kiowa decorated their tipis with designs, such as society or family symbols (McCready 1998; McAllister 1949). The Kiowa were excellent leather craftsmen who made elaborate clothing with only minimal bead decorations. The Kiowa culture also created calendars on animal hides to keep accurate records of tribal movements, gatherings, and environmental observations. The environmental observations, which are temporally and factually precise, have been cross-referenced with tree ring dates. The Kiowa and Kiowa-Apache traded extensively across the Great Plains region and were well known throughout the region as horse and slave traders. The tribe was known to trade with the Arikara, Hidatsa, and Mandan in the north and the Rio Grande Pueblo groups of New Mexico in the southwest. The Kiowa were notorious raiders who raided horses and cattle from across the southwest region from Arizona to northern Mexico to southeast Texas (Levy 2001).

Although the Kiowa were living as far south as Texas, New Mexico, and Oklahoma by the nineteenth century, the tribe is known to have spent significant time in the northeastern Wyoming and the Black Hills. The tribe’s migrations southward from Montana took them through this area, where they lived and hunted for some time. Archaeological evidence suggests, but without certainty, that the tribe used the Vore bison jump near Sundance, Wyoming (Reher and Frison 1980). Devils Tower has been regarded by historical (and contemporary) Kiowa as a major sacred site (San Miguel 1994), and figures in a number of their stories. In addition, there are several stories in Kiowa oral tradition that describe other features within northeastern Wyoming, connecting to the use of this region by the tribe at some point in their past (Harrington 1939:174-176; Sundstrom 1996:3c-5, 3c-7; Tsonetokoy 2002). These references to local landmarks, however, are specific to distinct landmark features such as Devils Tower or Bear Butte, and not to general features within the natural landscape. See Figure 10 for historic territories occupied by the Kiowa and Plains Apache; note that these may not include all areas used by them.

TRIBAL RESOURCES

Kiowa and Kiowa Apache Tribe

Kiowa Tribe of Oklahoma

100 Kiowa Way

Carnegie OK 73015

580.654.2300