The Hidatsa are part of the Siouan language family, closely related to the Mandan and Crow. The Hidatsa are thought to have occupied the Upper Missouri River valley and are documented as having occupied three villages at the mouth of the Knife River toward the end of the eighteenth century (Stewart 2001).

The Hidatsa and Crow Tribes are believed to have split from a common ancestral tribe. The split was first documented by the eighteenth century fur trader, La Verendrye (Hanson 1986), but most likely occurred sometime between 1675 and 1750; although, it is possible it occurred even earlier as oral traditions claim that it did. Oral traditions of both tribes relate the separation to an argument over bison meat, a primary subsistence food for both groups, as well as most tribes in the Great Plains. This occurred before the “Crow acquired the horse” (Foster 1993). Even after this separation, early accounts show the Crow and Hidatsa maintained good relations with frequent visits to each other’s tribes (Ewers 1997). Like the Arickaras, the Hidatsa are distinct from many other tribes of the Plains in that they traditionally practiced semi-sedentarism of fixed earth lodges, possessed fired ceramics, and practiced horticulture.

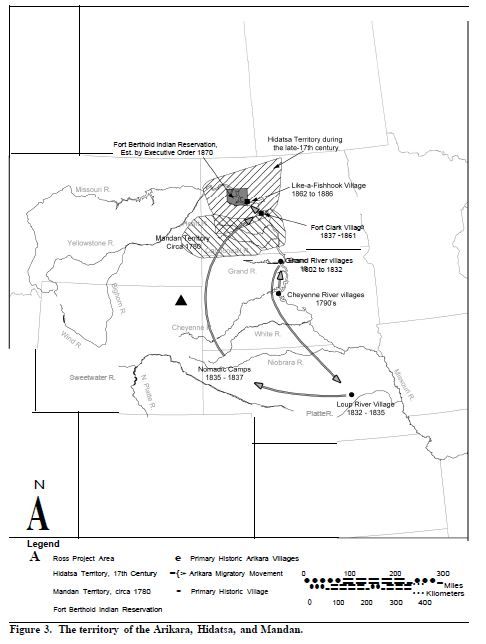

The Hidatsa people were divided into three groups: the Awatixa, the Awaxawi, and the Hidatsa proper. Although culturally and linguistically similar, each group tended to live in separate villages in the Knife River region in the Missouri River valley (Aher et al. 1991) (See Figure 3).  Oral tradition indicates that the Awatixa always lived on the Missouri River while the Awaxawi and the Hidatsa proper arrived from the east sometime after A.D. 1100 (Stewart 2001). A series of smallpox epidemics severely reduced the number of Hidatsa living in villages along the Missouri River and left them highly susceptible to attacks from the Lakota and Assiniboine (Stewart 2001).

Oral tradition indicates that the Awatixa always lived on the Missouri River while the Awaxawi and the Hidatsa proper arrived from the east sometime after A.D. 1100 (Stewart 2001). A series of smallpox epidemics severely reduced the number of Hidatsa living in villages along the Missouri River and left them highly susceptible to attacks from the Lakota and Assiniboine (Stewart 2001).

The Xoska band is reported to have spent considerable time in the “Rough Country” of the Powder River Basin. The band’s name, in fact, is derived from the Lakota word Hóski meaning Rough Country. This name was applied to these Hidatsa by the Lakota because of their use of the badlands in the Powder River Basin (Garcia 1998 [as cited in UW 2003]).

The Fort Laramie Treaty in 1851 established the boundaries for territories held collectively by the Hidatsa, Mandan, and Arikara. In 1870, when the U.S. government established the Fort Berthold reservation, the tribes were relocated to lands that disregarded the boundaries set forth in the Fort Laramie Treaty (Meyer 1977). At its inception, the Fort Berthold Reservation marked its southern boundary at the “junction of Powder River with the Little Powder to a point on the Missouri four miles below Fort Berthold” (Meyer 1977). Over the following decades, the reservation lands were reduced significantly until the reservation centered on Fort Berthold.

The Hidatsa people currently reside on the Fort Berthold Reservation alongside the Mandan and the Arikara tribes. All three tribes are referred to today as the Three Affiliated Tribes. Fort Berthold Reservation is located southeast of Minot and northwest of Bismarck, North Dakota.

The Hidatsa people combined both horticulture and hunting for subsistence. The tribe hunted big game, such as deer and elk, but pursued bison as their primary animal food source. The Hidatsa supplemented their animal foods with fish. The Hidatsa were intense horticulturalists whose cultivation of corn, beans, sunflowers, and squash was done primarily by women (Hanson 1986). Planting in the spring, the Hidatsa harvested the ripe corn in late September or early October, when it was ceremoniously braided and hung to dry (Lowie 1954). They stored the harvest, as well as dried meat and personal objects, in large “jug pits,” underground pits shaped like bells. The Hidatsa males also grew a form of ceremonial tobacco that they traded with the Crow who used it ceremonially, in comparison to the tobacco the Crow themselves cultivated (Lowie 1954). The Hidatsa’s annual subsistence cycle also involved seasonal migrations between camps during the fall and again during the summer to conserve access to fuel sources. Fall campsites tended to be located in “densely wooded river bottoms” (Stewart 2001) while in the summer, the Hidatsa returned to their earth lodges along the Missouri River. These seasonal migrations coincided with communal bison hunts. Prior to horse availability, the tribe used dog travois extensively to carry people, most often young children, and household goods during the seasonal migrations.

Not unlike other tribes, religious belief and ceremony permeated every aspect of Hidatsa daily life. It was believed that significant achievements of an individual in the tribe were the result of that person accessing supernatural powers, bestowed by supernatural beings who were themselves associated with animals. These supernatural powers could be attained in one of two ways: either by “fasting, self-torture, of by a combination of the two;” or by purchasing the power from someone else (Stewart 2001:335). Power in this sense was symbolized through the possession of sacred bundles, which could be transferred between individuals through elaborate ceremonies. A ceremonial feast for a bundle was initiated when an individual promised to honor the spirits in order to obtain supernatural power. While some of these ceremonies benefited only a very few individuals, others “serve all the people for instance by bringing buffalo or by causing rain” (Stewart 2001:336). Not only did individuals possess bundles for their own benefit, but also possessed tribal bundles which influenced the fate of the tribe as a whole.

The Hidatsa performed a number of ceremonies and rituals throughout the year. Many of these rituals not only revolved around the transfer and acquisition of bundles, as described above, but also involved rituals supporting such activities as planting and harvest, hunting, fishing, and warfare.

The Hidatsa village was a highly endogamous institution that was led by a council of elders whose meetings were open to participation from all members of the community. The village was further lead by two chiefs, the War Chief, a temporary position that may have only been filled in times of need, and the Peace Chief, the elder of the village with the highest ceremonial status, usually symbolized by the Earthnaming Bundle, particularly among the Awaxawi (Stewart 2001). The office of the Peace Chief, and the bundle, were generally inherited. After the smallpox epidemics of 1781 devastated the Hidatsa population, the three villages organized a pan-tribal council made up of warriors who oversaw matters of conflict with outside groups as well as maintaining good relations between the three villages.

The Hidatsa kin networks were organized by a matrilineal system recognized through clan, moiety, and phratries (Lowie 1954). There were seven clans in the Hidatsa tribe, each of which was divided into two moieties. Tribal clans provided social support for its members, especially for the elderly and those who had been orphaned (Stewart 2001). Equally important, the Hidatsa also used the age grade system. This system contained a number of men’s and women’s societies, age-cohorts were organized by coevals along gender lines. These groups seem to have been fraternal societies in general with few ascribed responsibilities, with the exception of the Black Mouths, a cohort of young men just below the age of the elder council. It was the responsibility of the Black Mouths to ensure that the decisions of the council were carried out. The women’s age-grade societies were fewer in number, and generally participated in activities that supported and celebrated the warring activities of the village men. The women’s societies were also more distinctly religious than that of the men. For instance, the Goose Society, with an age cohort of women ranging from 30 to 40 years of age, was responsible for ensuring a good harvest, while the similar White Buffalo Society sought to ensure the successful procurement of bison during the winter months.

As might be expected, marriage practices played a key role in the functioning of the tribe. Women were the core of the household, literally and figuratively. Not only did women build the earth lodge in which the family lived, but they owned the gardens, household goods, and animals, as well as passed on skills and knowledge from one generation to the next. The Hidatsa were a polygynous tribe, primarily sororal, with the men marrying the sisters of the same household. Men were expected to support their wife’s household through hunting, but still belonged to the household of their mother, which a man could also support and draw resources from.

The Hidatsa lived in earth lodges that were circular and dome-shaped. The roof was covered with earth and could be conical shaped or flattened at the very top (Lowie 1954). These earth lodges were intended to be permanent dwellings and could be used for 7 to 10 years. Beside each earth lodge was a cache pit that was used for the storage of dried meat and berries (Lowie 1954).

Like many semi-sedentary tribes, the Hidatsa manufactured a variety of tools for daily use. Agricultural tools, such as hoes, rakes and digging sticks, usually were made from bone or antler (Lowie 1954). Food gathering and storage, as well as heavy labor were made possible through the use of baskets. The Hidatsa were known to make two types of baskets, each from different natural materials. One type, the burden basket, was made from skins and was used to carry heavy loads, such as rocks or dirt excavated during the construction of their buildings. The other type of basket, the harvest basket, was made from willow bark (Lowie 1954). Basket making was a female craft, the skills for which were passed from one generation to the next. This knowledge may have had similar function as the bundles, which were primarily possessed by men, and may have been passed through similar ceremonies (Stewart 2001).

The Hidatsa also built small round boats known as “bull boats” that were made from bison skins. Women could easily carry these lightweight boats on their backs during portages. When bison herds were greatly reduced, bullboats were constructed from cowhide rather than bison (Lowie 1954).

The traditional territory of the Hidatsa from the 1780s until 1894 was located in northwestern North Dakota. Contemporary Mandan and Hidatsa people, however, recall the importance of the Powder River Basin through the boundaries of their historic territory as outlined in the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851, and through the activities of a separatist band known as the Xoska who lived in the area (Baker 2002; Driver 2002; Garcia 1998; Grinnell 2002; Hudson 2002 [as cited in UW 2003]). Oral traditions of all three groups of Hidatsa anchor the tribe to the Missouri River Basin. The sedentary lifeways of the Hidatsa made the tribe vulnerable to both disease and attacks by more nomadic tribes, causing them to condense their territorial range in the nineteenth century.

TRIBAL RESOURCES

Hidatsa Tribe

Three Affiliated Tribes

404 Frontage Road

New Town, ND 58763

701.627.4781