The three main groups in the tribe are the Pikuni or the Piegan, Kainah (Many Chiefs) or the Blood, and the Siksika or the Blackfeet (Ewers 1958; Schoenberg 1961). The Piegan occupied the western portion in the mountains of their territory with the Blood northeast of Piegan and the Northern Blackfeet northeast of the Blood (Martin 2005). All of the three groups are known as the Blackfeet, or the Siksika, and make up the Blackfeet Confederacy (Dempsey 2001). All three major divisions of the Blackfeet Nation speak an eastern Algonquian language. Algonquian derived languages were spoken among the eastern tribes of Native Americans, and was shared by several groups of Plains tribes who migrated westward during the early historic period. Linguistically, the Blackfeet appear to have been among the earliest Algonquian speakers to make the westward journey. Isolation from other Algonquian speaking groups and exposure to Shoshonean, Athapascan, and Siouan languages changed the Blackfoot languages; although, many similarities remained with Algonquian speaking tribes that would follow over the next two centuries. The division between the three Blackfoot tribes likely occurred during the westward migration resulting in some language differences arising between the groups (Ewers 1958). Although linguistically similar, these groups were politically and socially independent of one another. During prehistoric times, the three groups would come together for communal hunting purposes, warfare, and religious ceremonies.

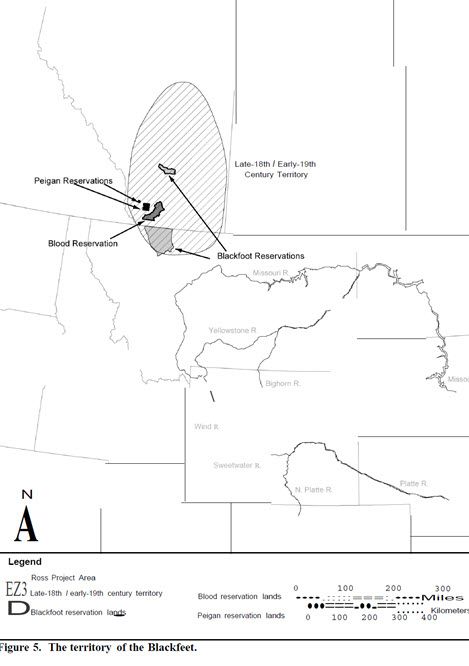

It is believed that the Blackfeet migrated out of the eastern woodland areas of Minnesota and Manitoba in Canada during the mid-1700s and occupied a large territory that stretched from the Northern Saskatchewan River in Canada to the Missouri and Yellowstone Rivers in Montana and up to the base of the Rocky Mountains (Martin 2005) (Figure 5). The specific reasons for the westward migration are not known, but it is likely that the Blackfeet were pushed west by rising populations of eastern tribes. By the 1800s, the Blackfeet recognized a smaller area that stretched from extreme northern Montana northward to the Saskatchewan River near Edmonton in Canada.

Before acquiring the horse, the highly mobile Blackfeet used dogs for work, transporting goods, and trade (Ewers 1958). Horses, called “elk dogs” by the Blackfeet, were introduced sometime during the 1730s when the Shoshone used them in warfare against the Blackfeet (Ewers 1958).

Before acquiring the horse, the highly mobile Blackfeet used dogs for work, transporting goods, and trade (Ewers 1958). Horses, called “elk dogs” by the Blackfeet, were introduced sometime during the 1730s when the Shoshone used them in warfare against the Blackfeet (Ewers 1958).

During their westward migration, trade with other Plains tribes introduced the Blackfeet to horses and other European trade goods which were moving west along with the fur trade. Soon after, the Blackfeet worked to obtain horses from surrounding tribes, such as the Flathead and the Nez Perce and obtained firearms from the Assiniboine and Cree (Ewers 1958).

The Blackfeet capitalized upon their new equine mode of transportation to move more easily throughout their territory and began to move into new areas in Shoshone territory (Dempsey 2001). Horse use allowed the Blackfeet to hunt more easily, and carry more goods. It also increased conflicts with neighboring tribes as hunting territories began to overlap and the desire for horses increased inter-tribal raiding. By the mid-1750s the Blackfeet began trading directly with the Hudson’s Bay Company, which had already established relations with both the Assiniboine and Cree (Dempsey 2001; Ewers 1958). Trade with the British typically involved Blackfeet travelling to British trading posts. A number of trading posts between the Missouri and North Saskatchewan Rivers were established between 1750 and 1850 (Ewers 1958). When the Americans began to travel up the Missouri River, their preference for trapping and hunting independent of the Native Americans led to several conflicts (Dempsey 2001).

Both peaceful and violent interactions with westward pushing Americans resulted in a series of treaties and agreements which defined the boundaries of Blackfoot territory, as summarized in the Ethnohistory of Wyoming’s Pumpkin Buttes (Philips et al. 2006):

Although not present at the original signing, the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 assigned lands to the Blackfeet from the Musselshell River, north of Billings, Montana, to the mouth of the Missouri River, west along the Rocky Mountains and back up north to the U.S./Canadian border (Ewers 1958). This huge extension of their southern border quickly became a source of conflict for many Plains tribes who recognized this region as their own hunting territory (UW 2003). This increased territory also may have allowed the Blackfeet to gain access to newer regions through their association with the Crow and Sioux tribes, who engaged in intertribal warfare and raids in the Plains region extending from northern Montana and into southern Canada (UW 2003).

As conflicts arose from the newly assigned lands, the Blackfeet met with representatives of the U.S. government and signed a treaty in 1855. Lame Bull’s Treaty, as the Blackfeet called it, was not agreed upon by all members of the tribe (Ewers 1958). This first treaty led to a series of later treaties, agreements, and executive orders that eventually picked away the original reservation to which the Blackfeet were assigned. Once the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 passed and the sale of tribal land allotments ended, the U.S. government provided the Blackfeet with only part of their original treaty lands that previously had comprised the greater Blackfeet Confederacy. As a result, the Blackfeet were placed on four reservations, three of which are located in Alberta Canada. The Piegan band was split into two divisions, with the northern division settling in Canada and the southern division settling on the Blackfeet Reservation in Montana (Martin 2005).

The Blackfeet Reservation located in Cut Bank, Montana, borders the Canadian province of Alberta and shares its western border with Glacier National Park. Badger Two-Medicine and the Lewis and Clark National Forest make up its southwestern border. The Blackfeet reservation consists of the Southern Piegan band of the Blackfeet Tribe in Montana while the Northern Piegan band is located across the border in Canada. North and South Piegan are known as Canadian and Montana Blackfeet, respectively. The rest of the Blackfeet Confederacy lives in Canada on three separate reservations named for their bands. (Phillips 2006:65)

The Blackfeet were almost exclusively bison hunters, though they also took advantage of the presence of other game, when bison were not present, and also hunted deer, antelope, and grizzly and black bears (Dempsey 2001). Smaller game consisted of porcupine, rabbit, and squirrel. Birds and fish were eaten only during stressful times (Wissler 1910). Plant foods utilized by the Blackfeet included a number of available species including serviceberries and chokecherries, wild turnips, rosebuds, and prickly pear (Dempsey 2001). Serviceberries and chokecherries in particular were used along with meat and bison fat to create pemmican, which could be kept for several months (Dempsey 2001).

During the “dog days” before they acquired the horse, the Blackfeet used several approaches for hunting bison. One method included luring or driving buffalo into surrounds formed either naturally using horses and people, or using corrals formed of poles set in the ground. Once surrounded, the buffalo could be killed with spears and arrows (Dempsey 2001). Another method was the bison jumps where the Blackfeet hunted bison in groups large enough to herd the bison into runs leading over a precipice. Bison by the hundreds fell off the precipice and were killed (Bradley 1923). The most commonly used bison jump, Head-Smashed-In, was located in southern Alberta, Canada (Thomas 2000). Once the tribe began using horses, their method of hunting changed to take advantage of their increased mobility and speed. Individual Blackfeet hunters would ride into the bison herd and single out their own animal to kill at close range (Ewers 1958).

The Blackfeet believed in a number of supernatural beings or forces that permeated all things on earth and in the heavens. Napi, for example, was believed to have created the world and everything on it. The Blackfeet believed that Napi lived in the mountains at the headwaters of the Oldman River in the province of Alberta, Canada (Ewers 1958). The Blackfeet also believed that the Sun was the supreme deity and that his power was important for success in war and in hunting. The Sun was married to the Moon, and the two of them had a son, represented by the morning star (Grinnell 1892). Supernatural forces in the ground or in the water generally were considered to be evil (Dempsey 2001).

Communication with the spirits was possible through ceremonies, prayer, dreams, offerings, and through medicine bundles (Harrod 1997). Medicine bundles were especially highly valued for their strong powers. They assisted individuals in their vision quests and were integral to certain ceremonies, particularly those such as the Medicine Lodge, which was used by warrior societies in the early nineteenth century (Dempsey 2001; Wissler 1918).

The Blackfeet believed that certain features in the landscape were sacred either because of their inherent powers or because of some event or use of that feature. For example, sacred places included areas where an individual had received a vision, ceremonial sites, burial sites, and sites used for sweat lodges. Some places were inherently sacred such as the whole range of the Rocky Mountains, which was considered to be the backbone of the universe (McClintock 1910).

The basic unit within the tribe was the band, comprised of related kin. Each band had several headmen and usually a band chief. Band chiefs were selected for their prowess as warriors and their generosity toward the poor. Responsibilities of the band chief included maintaining order within the band, settling disputes, acting as a mediator and magistrate, and maintaining good relations with other bands. Because band membership was fluid, members of a particular band could easily move from one band to another when political and social tensions grew too high (Harrod 1971; Martin 2005).

Polygyny was common among the Blackfeet with wealth of the husband being the limiting factor as to the number of wives a man could have. It was not uncommon for a man to marry the sisters of his wife and the widows of his brothers (Dempsey 2001).

Men and Warrior societies were an integral part of Blackfeet society; each society had its own rituals and responsibilities. These societies were age-based and members of these societies were selected at the early age of five and six years old. Young men in these societies were expected to learn the rules and customs from the older members. Older men in these societies organized hunts, raids, and relocations of the band. Hunting and war etiquette was strictly enforced by warrior societies who also maintained the social order of Blackfeet bands. Warrior societies often would organize and enforce gift giving to the survivors of a person’s family who was lost in battle or at other times. In 1833, seven of these men’s societies were still in existence. Men’s societies predominated with only one woman’s society being documented (Martin 2005).

Blackfeet material remains from pre-horse days are scarce due to their highly mobile lifestyle and lack of heavy burden animals. After the tribe began using the horse, however, individuals began to accumulate a few more items. It is difficult, however, to distinguish these items from those of neighboring tribes, especially the Gros Ventre, because the Blackfeet borrowed heavily from the technology and material cultures of their friends and enemies (Ewers 1958). The Blackfeet were known to have produced clay pottery for cooking and food preparation, but few remains have been found (Thomas 2000).

Perhaps the most common component of Blackfeet material culture was their artistic use of animal skins. The skins of buffalo and other animals were used for a number of purposes including clothing, coverings for tools and shields, domestic items such as cups and spoons, and coverings for their tipis (Ewers 1958). It was not uncommon for these items to be decorated in some fashion. Other animal parts also were used such as porcupine quills for clothing decoration and art. Their mobile lifestyle necessitated that they carry few objects, hence their preference for decorating items to be used on a daily basis or for ceremonial purposes (Scriver 1990).

After the Treaty of 1855, the Blackfeet were designated an extensive territory, reaching south to the Musselshell River. Although the U.S. government quickly reduced these lands, the Blackfeet may have entered into the northern most part of what is now Wyoming on raiding or hunting excursions. But the Blackfeet are not known to have used the lands in the region in a significant way. See Figure 5 for historic territories occupied by the Blackfeet; note that these may not include all areas used by them.

TRIBAL RESOURCES

Blackfeet Tribe

640 All Chiefs Road – Tribal Headquarters

Browning, MT 59417

406.338.5441