The Assiniboine are a Siouan-speaking people closely related to Sioux and Stoney Tribes. The Assiniboine oral tradition states that they emerged as an independent tribe in the seventeenth century when they broke off from the Yanktonai Sioux (Keating 1824; Mooney and Thomas in Hodge 1907-1910). The Stoney Tribe developed from the Assiniboine and became an independent tribe in the eighteenth century. Assiniboine is spoken in two distinct but mutually intelligible dialects. One is spoken predominantly on the Fort Belknap Reservation, and on the Grizzly Bear’s Head and Carry the Kettle reserves in Saskatchewan. The other dialect is spoken on the Fort Peck Reservation in Montana and the Ocean Man, Pheasant Rump, and White Bear reserves in Saskatchewan (Parks and DeMallie 1992). The Assiniboine call themselves the Nakota, the common name known among all Siouan tribes (Denig 1930; Parks and DeMallie 1996). The name Assiniboine comes from the Ojibwa term for ‘stone enemy.’ Many other neighboring tribes refer to them as the “Stones,” “Stone People,” and more commonly as the “Stone Sioux” (DeMallie and Miller 2001). This may have also derived from the Chippewa name of “those who cook with stones,” which comes from the Assiniboine’s practice of cooking with hot rocks.

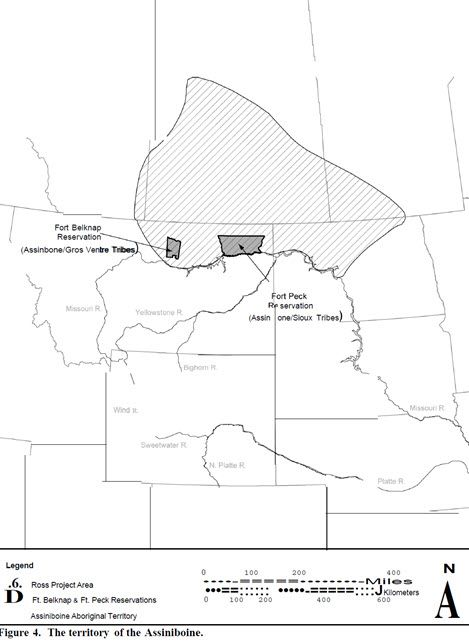

The traditional territory of the Assiniboine stretched from Lake Winnipeg in central Manitoba west to the plains of central Saskatchewan, south to the Missouri River and north of the North Saskatchewan River (Figure 4). In 1808, eight bands of Assiniboine were recorded and only one was found to be living within U.S. territory near the northern border of North Dakota. By 1840, two-thirds of the tribe was living along the western reaches of the Missouri River (Ray 1974). In the mid-nineteenth century the Assiniboine territory stretched east to west between Wood Mountain in southwest Saskatchewan, and the Cypress Hills, up to the North Saskatchewan River, and south to the Missouri River.

The first historical account of the Assiniboine as an individual tribe comes in 1640 when the tribe is described as living 100 miles north of Lake Nipigon, in present day Ontario, Canada (Wedel 1974; Ray 1974). The first European contact occurred in 1678 when English traders attempted to make peace between the Assiniboine and their Sioux neighbors to facilitate a larger trade network. This action was unsuccessful but the traders were able to trade with more tribes using the Assiniboine and their Cree allies as middlemen. The Assiniboine and the Cree were not peaceful with one another in the 1600s. At that time the Assiniboine were still closely tied to the Sioux tribes of Minnesota and the Eastern Plains. As the Cree began to acquire firearms from English traders they intensified their hostilities against the Sioux and their allies. The Assiniboine bore the brunt of these attacks due to their geographic proximity to the Cree. Seeing the vulnerable position they were in, the Assiniboine made peace with the Cree and began to intermarry with them. The Assiniboine gained access to European trade goods including firearms, but their relationship with the Sioux suffered (DeMallie and Miller 2001). European traders recorded open hostility between the Sioux and the Assiniboine in the late 1600s and early 1700s, prompting the peace making attempts mentioned earlier.

The Assiniboine utilized their relationship with the Cree to become part of the fur trade network of the Hudson’s Bay Company. The Assiniboine and Cree were the exclusive middlemen between the Hudson’s Bay Company located along the shore of Hudson’s Bay in northern Canada and the Northwestern Plains tribes of Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Montana. Original trade methods included porting massive shipments of goods by canoe up and down the rivers of the region. Seeking to maximize this middleman position, the Assiniboine began to expand their territory west into central Saskatchewan and central Alberta in search of beaver sources (Ray 1974). This brought some bands of the Assiniboine into competition and conflict with the Gros Ventre and Blackfeet tribes. At the same time, other Assiniboine bands were focused more on exploiting bison resources of the Northern Plains and were living peacefully with these same tribes (Ray 1974).  This westward movement of the Assiniboine may have also been motivated by pressure from the south and east from the Sioux tribes of North Dakota and Minnesota. By the mid-eighteenth century the Sioux had acquired firearms from French traders and had begun an aggressive push northward into Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Montana, the center of Assiniboine, Cree, and Ojibwa territories.

This westward movement of the Assiniboine may have also been motivated by pressure from the south and east from the Sioux tribes of North Dakota and Minnesota. By the mid-eighteenth century the Sioux had acquired firearms from French traders and had begun an aggressive push northward into Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Montana, the center of Assiniboine, Cree, and Ojibwa territories.

Horses began to be acquired by the Assiniboine in the mid-1700s. Trade with Blackfeet and Gros Ventre had provided many horses in the 1750s. However, a European explorer in 1755 found the Assiniboine using horses for material transportation and not yet riding them (Ray 1974; Hendry 1907). In 1776, the Assiniboine were known for their large horse herds but this was short lived (Ray 1974). In 1778, the Hudson’s Bay Company built the Hudson House trading post within the Gros Ventre tribe’s territory along the North Saskatchewan River near the town of Prince Albert. This eliminated the middleman position the Assiniboine had enjoyed for so long, and led to a huge increase in inter-tribal violence. At about this same time, the Assiniboine began to migrate south, settling along the modern Canadian-U.S. border. The Assiniboine and the Cree began to attack the Gros Ventre and Blackfeet throughout Saskatchewan and Montana, driving the two tribes south into northern Montana (Fowler 1987). This new hostility toward their main horse providers consequently led to the Assiniboine becoming extremely horse poor by the early 1800s. A report in 1830 stated the Assiniboine had at most two horses per household and relied on dog travois for transport.

The Assiniboine were hit hard by a smallpox epidemic between 1781 and 1782. It is reported that one-third to half the tribe died from the outbreak (Denig 1930; Ray 1974; Miller 1987). In response the survivors began to move south, again attracted by new trade opportunities with the Mandan tribe and plentiful buffalo along the Missouri River. The Assiniboine began to trade with the American Fur Company and with Spanish traders from Louisiana who had moved up the Missouri River, providing guns and other European goods. A large number of Assiniboine began settling in the Fort Union area along the Missouri River at the modern North Dakota- Montana border. This location sheltered the tribe from attacks by neighboring tribes and provided access to new trade networks but exposed the tribe to the diseases of the white traders. The tribe began to rebound from its population losses in the late 1700s only to be devastated again by a smallpox epidemic in 1837-1838, transported from Saint Louis by an infected trader steamboat. Of the reported 250 lodges at Fort Union at the time, only 30 lodges survived (Miller 1987; Denig 1930). This terrible loss left the survivors vulnerable to attacks from all the surrounding tribes; the Plains Cree remained the Assiniboine’s ally (Denig 1961).

The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 granted the Assiniboine hunting rights on Blackfeet lands at the mouth of the Milk River in northern Montana, just west of the present-day location of the Fort Peck Reservation. This region was shared with the Blackfeet, Gros Ventre, Crow, and bands of Métis who had moved south from Canada. The restriction of land use and the competition for dwindling resources eventually led to further conflict. The U.S. government eventually established Fort Browning in 1869 in the current Fort Belknap Reservation area (DeMallie and Miller 2001). Fort Browning became an annuity distribution center for several tribes of the region. This fort lasted 4 years and was abandoned when tensions between tribes using the fort and surrounding region for hunting turned violent. Fort Belknap and Fort Peck were opened a few years later to redress matters (Flannery 1953).

The Assiniboine separated into individual bands after the disintegration of Fort Browning and several violent encounters between other tribes, white hunters, and settlers. Some moved west to live peacefully among the Blackfeet and Gros Ventre tribes (Flannery 1953). Many stayed with the Yanktonai Sioux and became part of the Fort Peck Reservation, officially established in 1886 (Flannery 1953). Those that moved west became part of the Fort Belknap Community with the Gros Ventre tribe. Many other smaller bands returned north and claimed lands in central and southeastern Saskatchewan. These were negotiated with the Canadian government in 1874 and throughout the late 1800s. The bands that remained in the U.S. were divided as the Upper Assiniboine and Lower Canoe Paddler Assiniboine bands. The Upper bands included the North, Stone or Rocky, and the Dogtail bands. These bands were located in the Fort Belknap area south of Chinook, Montana. The Lower Canoe Paddler bands included Red Stone, Broken Arm, Bobtail Bear, and Red Snow bands. These bands occupy the Wolf Point area of the Fort Peck Reservation, which they share with the Yanktonai Sioux (DeMallie and Miller 2001).

Bison were the mainstay of the Assiniboine Tribe’s diet. The tribe would congregate and disperse according to the seasonal pattern of the bison herds. The tribe generally used three methods of bison hunting. The first was to systematically surround the herd with 80 to 100 hunters on horseback who would fire arrows at the herd animals. This method would kill 100 to 500 buffalo in an hour (Denig 1930). The second method was the pound or park method in which coordinated hunters would drive a herd over a cliff or bluff where they would fall into a corral at the bottom. The bison were then slaughtered with arrow and bullet fire. This method could provide 300 to 600 buffalo at a time. Several days would be required to butcher all of the meat. This method was utilized well into historic times. Three such pound areas were located near Fort Union (at the confluence of the Missouri and Yellowstone Rivers) in the early 1850s. Another method used was stalking, where a single hunter using a rifle would stalk and kill a single bison. This was often practiced in the winter when the bison herd and the tribe were dispersed (Denig 1930). The Assiniboine also hunted elk, deer, big horn sheep, and antelope. Grizzly bear were occasionally hunted, often in the winter in their dens. Killing a grizzly ranked just below killing a human enemy and was counted among a man’s brave deeds. Small game animals, including wolves and foxes, were hunted for their fur while a larger variety of small animals and birds were eaten. The diet was rounded with prairie turnips, wild rhubarb, artichokes, various fruits, berries, and rose hips (Denig 1930; Rodnick 1938).

Similar to the Sioux tribes, Assiniboine religion centered on the wakan (waka) or ‘holiness’, which represented all things wondrous. All life, and the elements of the world were considered spirits and manifestations of wakan. The creator, although not personified, was named Wakan Tanka (waka taka) or ‘great holiness.’ The spirits of wakan were omnipresent and omnipotent, but could be called on by humans for good or evil purposes. Through prayer, pipe offerings, sacrifices, weeping, and self-mortification, men could gain the pity of the spirits. Spirits were considered to be security for individuals in an unsecure world (Denig 1930). Vision questing was quite common, and was used to provide power for warfare, hunting, or curing. Some men, through repeated questing, gained powers of perception and healing. These holy men were responsible for leading ceremonies and defending people from evil medicine, including through herbal remedies and sweat baths. It was Assiniboine belief that evil medicine was shot into another person’s body over great distances. Women did not actively seek out wakan power, but it was sometimes endowed on them through dreams.

The most important ritual in Assiniboine culture was the Sun Dance. The Sun Dance was held in June with the gathering of the tribe during the summer bison hunts. Other rituals were performed by men’s societies such as the Horse or Fool society. The Fool Society (witkokax wacipi or ‘fool-maker dance’) held two-day events focused on hunting and war powers, but its members were also considered able healers of eye injuries. The Fool Society would wear masks, speak in a ‘backwards way,’ and imitate a trickster cultural hero. The Horse Society was considered as sacred as the Sun Dance, and included both men and women. Society members were trained in ceremonies and skills helpful in healing horses and people. The Society prayed for the acquisition of horses and for children to grow-up free of sickness (Rodnick 1938; Lowie 1909). Most other societies were men-only groups associated with powers of leadership and warfare. Women also had exclusive societies although little is known of them (DeMallie and Miller 2001).

The primary unit of the Assiniboine tribe was the band. Each band was comprised of extended families headed by a chief or ‘huka.’ The chief position was earned through merit and generosity; hence, wealth was a prerequisite for this position. There was no over-arching political structure above the band level. During major gatherings the tribe would camp in a large circle with each band occupying its own part of that circle, thus maintaining its own autonomy (Rodnick 1938). A band council was made up of male members who had achieved some success in battle. The band chief led the council, but he had little extra authority over its decisions. A portion of the council served as soldiers. The soldiers function was that of police, maintaining order within the camp and supervising hunts and camp movement. Punishment of transgressions usually resulted in the destruction of the person’s possessions. Crimes, like murder, were considered personal affairs dealt with by the families affected. Neither the Chief nor the Council would become involved (Denig 1930).

The Assiniboine were bison hunters and as such were highly mobile. The tribe’s relative lack of horses through much of the 1700s and 1800s required them to rely on the dog travois for much of their pre-reservation history (DeMaillie and Miller 2001). The Assiniboine built buffalo hide tipis with a three-pole foundation; although, Lewis and Clark reported that they used a four pole formation during their visit with the tribe (Lowie 1909). The average tipi was constructed of 12 hides and usually covered an area measuring 31 feet in diameter. The tribe’s close connection to the Hudson’s Bay Company in the late 1600s and 1700 resulted in the tribe having access to a number of European made metal tools, guns, foodstuffs, and alcohol. DeMaillie and Miller (2001:582) state that the tribe was less eager to use European goods especially clothing, and also that they had few guns, which put them at a disadvantage against their enemies. This assessment may refer to the period in the mid-1800s when the tribe had moved into northern Montana and North Dakota along the Missouri River and was temporarily cut off from European trade goods.

The most complete history of the Canadian Assiniboine is provided by Ray (1974), in which he focuses on the Assiniboine’s involvement in the fur trade. Histories of the Montana Assiniboine include Rodnick (1938) and Fowler (1987). Denig (1930) wrote ethnographic accounts in the 1850s on Assiniboine culture; Parks and DeMallie (1992, 1996) provide linguistic classification and an unpublished dictionary and collection of texts; Lowie (1909) provides descriptions of Assiniboine art and artifacts.

The tribe’s southernmost territory appears to have commonly reached only as far as the Milk and Missouri Rivers in northeastern Montana and is not known to have traditionally extended as far south as northeastern Wyoming. There is no reference in the literature regarding the Assiniboine in mention of the Bear Lodge, Inyan Kara, or any other landscape features associated with the Black Hills region. The extent to which they may have traveled as far as these lands is not specified. See Figure 4 for historic territories occupied by the Assiniboine; note that these may not include all areas used by them.

TRIBAL RESOURCES

Assiniboine Tribe

Fort Peck Assinboine & Sioux Tribes

PO Box 1027

Poplar, Montana 59255

406.768.2300