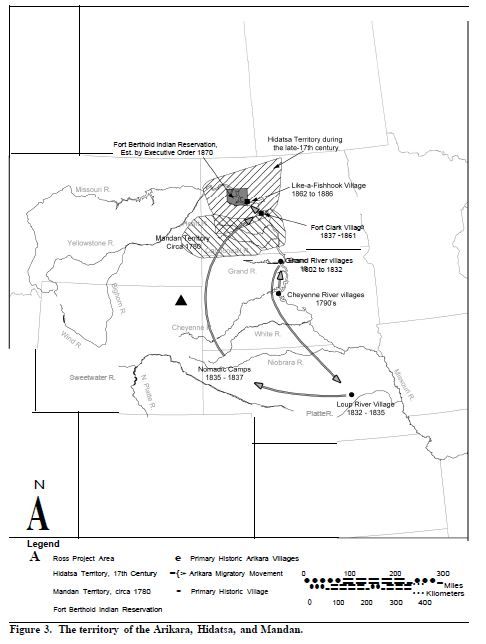

The Mandan are a Siouan speaking tribe that occupied the upper Missouri region (see Figure 3). The Mandan lived primarily along portions of the Upper Missouri River and eventually settled along the White Earth River, North Dakota (Will and Spinden 1906; Wood and Irwin 2001). Prior to European contact, the Mandan consisted of four bands: the Nuptadi or “east-side Mandan,” the Nuitadi or “west-side Mandan,” the Awigaxa and the Istopa or the “northern Mandan” (Meyer 1977; Bowers 1950). During the 1600s the four groups resided on the banks of the Missouri River, with the greatest concentration of villages near the mouth of the Heart River.

Prior to European contact, the Mandan, along with the Hidatsa, played a key role among the Plains tribes as middlemen in an extensive trade network. Their location at the “nexus of three trade routes,” as well as their semi-sedentary lifestyle, permitted them to trade in goods from most every region of North America (Meyer 1977). In addition, their sedentary and agricultural lifestyle made it possible for them to grow surplus crops to use in their trade negotiations. However, their position as traders was generally precarious. Pressure from more aggressive nomadic groups pushed them into strongly fortified villages along vast sections of the Missouri River from the Cannonball River to the mouth of the Yellowstone River (Bowers 1950; Wood and Irwin 2001) (See Figure 3). The Mandan villages were important trading centers for Native Americans in the Great Plains; this position was strengthened by the inclusion of European trade goods. By 1738, the Mandan replaced the Assiniboine as the primary middlemen in the trade networks between the Europeans and other tribes. Their success in trade, however, contributed to their undoing. Their strategic location along the major trade routes, as well as their frequent contact with the Europeans, critically exposed them to multiple smallpox outbreaks (Meyer 1977). Outbreaks in the late 1700s and in 1837 decimated the tribe. Their weakened state left them vulnerable to attacks from the Lakota and other tribes. In an effort to allay this onslaught, the Mandan formed an alliance with the Arikara and the two tribes began living together until they were strong enough to split up and establish their own villages again (Meyer 1977).

The Mandan villages were important trading centers for Native Americans in the Great Plains; this position was strengthened by the inclusion of European trade goods. By 1738, the Mandan replaced the Assiniboine as the primary middlemen in the trade networks between the Europeans and other tribes. Their success in trade, however, contributed to their undoing. Their strategic location along the major trade routes, as well as their frequent contact with the Europeans, critically exposed them to multiple smallpox outbreaks (Meyer 1977). Outbreaks in the late 1700s and in 1837 decimated the tribe. Their weakened state left them vulnerable to attacks from the Lakota and other tribes. In an effort to allay this onslaught, the Mandan formed an alliance with the Arikara and the two tribes began living together until they were strong enough to split up and establish their own villages again (Meyer 1977).

By the mid-1800s, the Mandan were on the move again, this time as a result of the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851, and the establishment of their reservation. The Fort Laramie Treaty established the boundaries for territories held collectively by the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara. The boundaries were described in the Treaty as “commencing at the mouth of Heart River; thence up the Missouri River to the mouth of the Yellowstone River; thence up the Yellowstone River to the mouth of the Powder River in a southeasterly direction, to the headwaters of the Little Missouri River, thence along the Black Hills to the head of the Heart River, and thence down Heart River to the place of the beginning” (Treaty of Fort Laramie 1851). In 1870, when the U.S. government established the Fort Berthold reservation, the tribes were placed on lands that disregarded the original boundaries set forth in the Fort Laramie Treaty (Meyer 1977). At its inception, the Fort Berthold Reservation marked its southern boundary at the “junction of Powder River with the Little Powder to a point on the Missouri four miles below Fort Berthold” (Meyer 1977). Over the following decades, the reservation lands were reduced significantly until the reservation centered on Fort Berthold.

Today the Mandan people reside alongside the Hidatsa and the Arikara tribes on the Fort Berthold Reservation. The three tribes are known collectively as the Three Affiliated Tribes. Fort Berthold Reservation is located southeast of Minot and northwest of Bismarck, North Dakota.

Because they lived a largely sedentary lifestyle, the Mandan relied upon horticulture to provide their primary food source along the Upper Missouri River. Crops regularly produced by the Mandan women included seven types of corn, as well as several types each of beans, squash, sunflowers, and melons for food as well as tobacco for ceremonial use (Lowie 1954; Thompson and Hopwood 1971; Will and Spinden 1906; Wood and Irwin 2001). The tribe supplemented their diet by hunting bison, elk, deer, antelope, and wild birds, fishing, particularly catfish, and by gathering wild fruits, such as chokecherries and wild plums. Although largely sedentary, the Mandan trapped in vast areas that included rugged lands between the Little Missouri River and Missouri River mainstem, and “as far west as Powder River in Montana,” their hunting grounds being nearly indistinguishable from those of the Hidatsa (Bowers 1950; Wood and Irwin 2001). Trapping grounds also included areas near the Cannonball River and sections of the Black Hills. Animals trapped by the Mandan included both bear and eagle for religious and ceremonial activities. Sedentism allowed the Mandan to increase their agricultural skills so that surplus crops became an important part of their trade with other tribes, and later, with European traders (Wood and Thiessen 1985; Meyer 1977). Early European explorers to the area noted the regularity with which other tribes, such as the Assiniboine, made seasonal visits to the Mandan for the express purpose to trade for corn and other agricultural goods (Lowie 1954).

Mandan religious life revolved around the male acquisition of power, such as through undertaking vision quests or procuring bundles. All aspects of the natural world possessed power, and, like many of the Plains tribes, the Mandan believed in a number of spirits with the First Creator being the most powerful of these. Their faith in the supernatural affected all aspects of their daily lives from agriculture to warfare and involved communication with the spirits in order to guarantee health and happiness for the village. Personal power was symbolized through the possession of bundles, which could be inherited, or assembled in conjunction with a vision quest. The Mandan communicated with the spirits through ceremonies, self-torture, and through meditation on their medicine bundles. Women as well as men could own, assemble, or get power from a bundle. A woman could also get power from a bundle that she then passed to her husband. The Mandan believed that the visions created by these activities opened direct communication with the spirits (Bowers 1950). The Mandan also valued individual kindness and philanthropy toward other tribal members (Meyer 1977). In fact, gift giving was considered the most prestigious and the most difficult way to earn the good favor of the spirits.

Of the many ceremonies that permeated Mandan daily life, perhaps none was more important than the four-day Okipa Ceremony, which had many parallels to the Sun Dance. This annual ceremony was a reenactment of the Mandan creation story and of the hardships that the Mandan people had endured over the generations (Bowers 1950). Good fortune, a bountiful harvest, and successful hunting were assured by the Okipa ceremony, which involved self-torture, dancing, and visions. Another important ceremony was the “Cleansing of the Seeds,” which the owner of the corn bundle held on his roof. In this ceremony special seeds were sanctified and distributed to the women of the village for planting. The owner of the corn bundle held the responsibility for assuring a good harvest, and did so throughout the growing season by performing the necessary rituals in response to the weather, whether too hot or cold, too dry or wet.

In accordance with the Okipa ceremony and origin myth, the Mandan are a group of thirteen exogamous matrilineal clans grouped into a clan and moiety system that was further delineated by age (Bruner 1955; Lowie 1912; Wood and Irwin 2001). The Mandan political system revolved around the village with individual members usually showing more dedication to their village than to the tribe itself. Moving one’s residence to another village was not uncommon; however, and individual loyalties transferred to the new village (Meyer 1977).

Leadership of the clan was determined by the clan members. Men gained status and position through their demonstrated success in warfare. Those individuals who had demonstrated bravery and gained prestige in battle and on hunts were most likely to be selected to partake in the decision making council of headmen (Wood and Irwin 2001). As with the Hidatsa, both a War Chief and a Peace Chief were selected as village leaders, the former based on performance as a warrior and the latter an inherited position and symbolized through possession of especially powerful bundles (Bowers 1950; Wood and Irwin 2001). Residence was matrilocal with matrilinearly related extended kin networks inhabiting the same lodge and sharing household goods. Ultimately, marriages were seen as unions between families, and were often made to unite clans or bring peace between villages in conflict. These unions were created through the exchange of gifts between the families (Lowie 1954).

The Mandan also maintained age-societies; although, the exact number of male societies is not documented. Women had four age-societies, the most prestigious of which was the White Buffalo Society, the membership of which consisted exclusively of women of post-menopausal age, and who were reputed to be highly skilled with healing and herbal medicine.

Mainly women in early Mandan society produced pottery. Mandan women had two techniques for producing pottery: the paddle and anvil and the coil method. The latter is less frequently utilized in the current day. Decorative patterns included check stamping, which involved creating decorative designs on the pottery by incising a crisscross pattern. Archaeological sites that contain pottery with check stamping have been located between the Heart River and just north of the Knife River (Neuman 1963). Hagan ware, a pottery style type attributed to the Mandan, has been found along the Missouri River in North Dakota. Additionally, a small variety of bone tools and utensils made from mostly from bison were for agricultural use and were utilized for daily activity.

The Mandan constructed earth lodges that were “covered with hard water-proof clay” (Meyer 1977; Catlin 1973) and that incorporated a hearth at the center of the structure. Lodge construction included rafters that extended slightly beyond the large central beams that left a small opening at the top. Horizontal poles were placed on top, leaving a small smoke hole in the center (Meyer 1977). Earth lodges were circular in form and varied in size from 30 to 60 feet depending on the number of occupants living in them. Earth lodges were divided into rooms that served various functions. Mandan earth lodges were constructed for semi-long term use, about 10 years. In Mandan society, every village center contained an open area known as the “Big Canoe,” the greatest source of power for the Mandan. The Big Canoe was associated with the Mandan oral history of a great flood (Catlin 1973). Other common structures found in the Mandan villages included ceremonial lodges, palisades, burials, mounds, and caches. Caches were simple pits dug out of the earth that may have been used for storage. Most caches found are approximately three feet deep (UW 2003).

Rock art and cloth paintings have been attributed to the Mandan culture, but can be indistinguishable from the work of other Plains tribes due to overlaps in style and technique. Examples of Mandan rock art include shield figures, which in general Plains art can be located in parts of Texas and New Mexico and as far north as Saskatchewan and Alberta. A similar range of rock art drawings, including shield figures, are found in the northern parts of Wyoming and Montana (Francis and Loendorf 2002; Gebhard 1966).

Mandan oral traditions cite the Missouri River as their sacred origin point. As a result of their increasing sedentism in the late seventeenth and eighteenth century, encouraged by external pressures of warfare and aggression, it is unclear to what extent their pre-seventeenth century territory ranged. The eastern most extent of their territory, in the late eighteenth century, reached approximately to the Powder River in southeastern Montana. As the tribe succumbed to the ravages of smallpox and intertribal warfare, their territory shrank considerably. The Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1851, however, did establish their territory as extending to the Powder River. These lands were reduced significantly in the years that followed. It has been reported by UW (UW 2003) that contemporary Mandan hold the Powder River in high regard based primarily, it appears, on the lands granted to them by the Treaty of Fort Laramie.

TRIBAL RESOURCES

Mandan Tribe

Three Affiliated Tribes

404 Frontage Road

New Town, ND 58763

701.627.4781