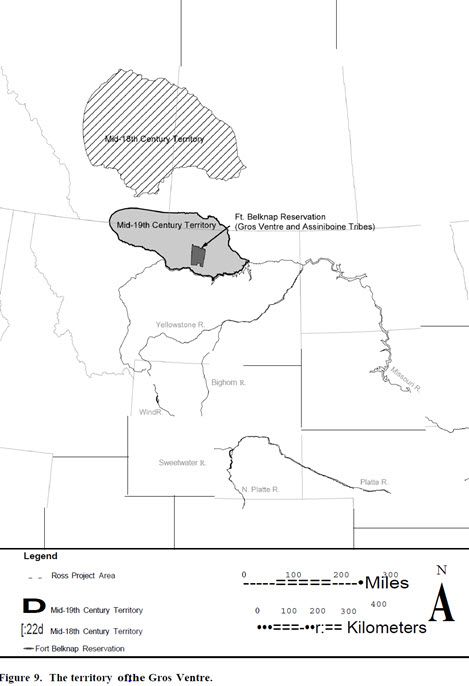

The Gros Ventre people speak an Algonquin language, closely related to the Arapaho language. It is widely believed that the Gros Ventre tribe was at one time part of the Arapaho tribe that had split off. It is unknown when or why these two tribes separated (Kroeber 1908). The Gros Ventre tribe was not clearly identified by Europeans until the mid-eighteenth century. At that time the tribe occupied the Canadian plains between the North and South Saskatchewan Rivers. The close similarities between the Gros Ventre and Arapaho languages suggests that the Gros Ventre may have moved from the east into the Saskatchewan region at a similar time as the Arapaho and Cheyenne migration out of the western Minnesota region. The name Gros Ventre means “big bellies” in French, and was a name given to them by French fur traders visiting the region. The Gros Ventre call themselves “’aa’ aaaniineninch” meaning ‘white clay people.’ This name refers to the lime or chalk used to clean hides, or the mounds of earth used to direct bison into corrals (Taylor 1983; Kroeber 1908). Many neighboring tribes refer to the Gros Ventre as the ‘always hungry’ (Fowler and Flannery 2001). Many of the Gros Ventre were also fluent in the language spoken by the Blackfoot, which alludes to the frequent interaction and usually friendly relations between the two groups (Morgan 2009).

The Gros Ventre people were confirmed to be encountered by Europeans historically in 1772 when Cocking (1908) an English trader met the tribe where then living between the two forks of the Saskatchewan River (Figure 9). Cocking called the tribe the “Waterfall Indians” and associated them with a group of five allied tribes known to the Cree as the Archithinue (Kehoe and Kehoe 1974). This group included the Gros Ventre, two bands of Blackfeet, and the Sarcee. In the early 1700s these five allied groups traded with the Cree, but at times they also were in conflict with the Cree and their allies, the Assiniboine (Isham 1949). The Hudson Bay-based fur trade industry of the 1600s and 1700s pushed westward closer and closer to the Gros Ventre territory with the Cree and their allies acting as middlemen in trade matters. Later the Hudson’s Bay Company would build camps and the Hudson House to trade directly with the Gros Ventre tribe. In the 1780s, the Gros Ventre experienced their first of many smallpox outbreaks. Coupled with the effects of the disease, the Gros Ventre also experienced increased conflict with several of their neighbors, notably the Blackfoot, who were their traditional allies, and the well- armed Cree. Conflicts with these tribes, coupled with the virulence of smallpox caused a great deal of Gros Ventre casualties. The Cree were well equipped with guns from their dealings with the European traders and began to pressure the Blackfeet and their allies, including the Gros Ventre, to move south. The Gros Ventre began to feel stressed and began to strike back at their Cree and Assiniboine enemies and at the European traders who the Gros Ventre viewed as the Cree’s allies. In less than 10 years the Gros Ventre tribe had gone from being considered “the most rational and inoffensive” to a dangerous tribe especially aggressive towards traders (Fowler 1987).

By the 1830s, the Gros Ventre had moved with their Blackfeet allies to live among the Cypress Hills in northern Montana and southern Canada. The tribe settled around the Milk River between the Missouri and Frenchman Rivers. The Gros Ventre and their allies were initially opposed to the fur traders in their new territory; however, relations improved and peaceful trade between the Gros Ventre and the American Fur Company along the Upper Missouri River began. The Gros Ventre became wealthy with horses and trade goods and partially escaped the smallpox epidemic in 1837, although losing 200 members—many fewer than neighboring tribes (Fowler 1987). In 1855 the Gros Ventre and their Blackfoot allies signed a treaty with the U.S. government allowing U.S. military travel and military posts to be built throughout their territory (Kappler 1904-1941). Increasing numbers of white settlers in the Upper Missouri River region restricted the hunting and travel of the Gros Ventre into smaller and smaller territories. The reduction in their hunting territory, and the dramatic U.S. deprecation of the buffalo herds across the Plains, severely impacted the lives of the Gros Ventre. Unable to procure buffalo in significant quantities, the tribe, along with the Assiniboine, who were suffering similar issues, began to consolidate around Fort Belknap in north central Montana. Fort Belknap was a substation outpost with a small trading post and blockhouse for distributing annuities from the government. As white settlers further pressed the tribe into smaller and smaller areas, the tribe began to rely more heavily on Fort Belknap for food and supplies. The government decided to close Fort Belknap 1876 and force the Gros Ventre tribe to travel to the Sioux reservation of Fort Peck for supplies. The Gros Ventre opposed being forced to mingle with their enemy, the Yanktonai Sioux, and refused to travel (Flannery 1953). They instead supplemented their food supply with local game. In 1878 the U.S. government re-established Fort Belknap, and the Gros Ventre and the Assiniboine again began to draw their annuities there. From 1878 to 1890 the Gros Ventre lived in four large groups west of Fort Belknap, to better defend themselves from Sioux and Blackfeet raiding parties. In 1890, the tribe lost much of their territory to the U.S. government, in return for the tribe being allotted a small reservation around Fort Belknap, which they shared with some bands of Assiniboine (Flannery 1953).

By the 1830s, the Gros Ventre had moved with their Blackfeet allies to live among the Cypress Hills in northern Montana and southern Canada. The tribe settled around the Milk River between the Missouri and Frenchman Rivers. The Gros Ventre and their allies were initially opposed to the fur traders in their new territory; however, relations improved and peaceful trade between the Gros Ventre and the American Fur Company along the Upper Missouri River began. The Gros Ventre became wealthy with horses and trade goods and partially escaped the smallpox epidemic in 1837, although losing 200 members—many fewer than neighboring tribes (Fowler 1987). In 1855 the Gros Ventre and their Blackfoot allies signed a treaty with the U.S. government allowing U.S. military travel and military posts to be built throughout their territory (Kappler 1904-1941). Increasing numbers of white settlers in the Upper Missouri River region restricted the hunting and travel of the Gros Ventre into smaller and smaller territories. The reduction in their hunting territory, and the dramatic U.S. deprecation of the buffalo herds across the Plains, severely impacted the lives of the Gros Ventre. Unable to procure buffalo in significant quantities, the tribe, along with the Assiniboine, who were suffering similar issues, began to consolidate around Fort Belknap in north central Montana. Fort Belknap was a substation outpost with a small trading post and blockhouse for distributing annuities from the government. As white settlers further pressed the tribe into smaller and smaller areas, the tribe began to rely more heavily on Fort Belknap for food and supplies. The government decided to close Fort Belknap 1876 and force the Gros Ventre tribe to travel to the Sioux reservation of Fort Peck for supplies. The Gros Ventre opposed being forced to mingle with their enemy, the Yanktonai Sioux, and refused to travel (Flannery 1953). They instead supplemented their food supply with local game. In 1878 the U.S. government re-established Fort Belknap, and the Gros Ventre and the Assiniboine again began to draw their annuities there. From 1878 to 1890 the Gros Ventre lived in four large groups west of Fort Belknap, to better defend themselves from Sioux and Blackfeet raiding parties. In 1890, the tribe lost much of their territory to the U.S. government, in return for the tribe being allotted a small reservation around Fort Belknap, which they shared with some bands of Assiniboine (Flannery 1953).

The Gros Ventre Tribe is part of the Fort Belknap Indian Community on the Fort Belknap reservation, located in north central Montana near the Little Rocky Mountains. The northern boundary of the reservation runs along the Milk River, a northern tributary of the Missouri River. The Gros Ventre tribe has shared the reservation with the Assiniboine tribe since inception of this reservation area in 1890. A constitution and by-laws were adopted by the tribe in 1935, but the federal government required that the two tribes be incorporated together, which occurred in 1937 after much resistance (Fowler 1987).

The Gros Ventre tribe depended primarily on buffalo hunting for subsistence. Before acquiring horses the tribe used impounding methods to hunt buffalo (Curtis 1907-1930; Flannery 1953; Kroeber 1908). After the horse was introduced the tribe would congregate into large groups of 300 to 500 people in anticipation of the bison’s northern migration. Groups of men with specially trained “buffalo horses” would make “runs” on herds firing arrows at the bison. Smaller groups or individuals stalked deer, elk, and antelope. Winter campsites were usually located along wooded creeks but in the summer a band would move several times to follow smaller herds of bison. All meat was eaten immediately, dried as jerky, or pounded into pemmican. Bison hides collected at specific times of the year were used for different functions. The hides taken in the spring with thinner hair were used more for tipi covers, moccasins, par fleches, bags, and ropes. Hides taken in the fall and winter when the hair was thickest were used for clothing and blankets. Women were responsible for the processing of hides, building tipis, making clothes and other domestic items, and gathering vegetables such as roots, berries, nuts, and tubers. Men were responsible for hunting larger game, skinning animals, and looking after horse herds.

The Gros Ventre traditionally believe in a single supernatural being known as “The One Above,” or ‘he who makes or does (by thought or will).’ This being is not thought of in a human form, and is considered the ultimate source of life and of the power possessed by other supernatural beings and humans (Cooper 1957). No tribal member in the nineteenth century recounted any origin or creation stories concerning “The One Above” within ethnographical accounts. However, three hero traditions were recorded. The heroes, known as Nih’atah, Earthmaker, and He Who Starved to Death, are said to have provided the Gros Ventre with many different gifts. Nih’atah gave the people freedom of thought and taught them to pray with a pipe. Earthmaker recreated the world after a flood and created the Flat Pipe medicine bundle, an important part of Gros Ventre ceremony. He Who Starved to Death used supernatural assistance to coax horses out of a lake to provide for the tribe.

Traditional Gros Ventre ceremony revolves around the upkeep of two medicine bundles known as the Flat Pipe bundle and the Feathered Pipe bundle. Keepers are specially trained individuals who have made prayer-sacrifice vows, such as providing gifts for the bundle, or sponsoring a sweat ceremony, care for these bundles (Cooper 1957; Horse Capture 1980). The Sun Dance ceremony was a central part of the Gros Ventre religious system but it was completely lost after the wide spread introduction of Catholicism (Horse Capture 1992). Christianity was introduced to the tribe in the late 1880s with the building of a Jesuit Mission in Hays, Montana. In the 1890s several converts of children and a few adults prompted more and more of the tribe to convert. Horse Capture (1992) attributes the converts to increased pressure from economic hardship; whereas, others suggest the conversions resulted from two other factors. Fowler (1987) cites similarities between Catholicism and Gros Ventre beliefs, specifically a Supreme Being and prayer sacrifice. Junkins (1889) states that the tribe was attempting to appeal to the Indian Agent, showing him they were becoming more civilized. Regardless of the reason, traditional Gros Ventre religious practice suffered. Lodge ceremonies, including the Sun Dance, began to disappear. In 1924 the last official Keeper died and by the 1930s only a small group of people still practiced the pipe bundle ceremonies, (Fowler 1987). In recent times, the tribe has begun to look for ways to rebuild their traditional religious practices. This has included borrowing or learning ceremonies from their past relations the Arapahos (Horse Capture 1992). The Flat Pipe and Feathered Pipe bundle ceremonies, and the instruction of Keepers are included in these ceremonies.

Another significant ceremony among the Gros Ventre was the Grass Dance. The dance was adopted by many of the Plains tribes; although, it is generally believed by the tribes themselves to have originated with the Gros Ventre. The ceremony takes place in a multi-sided building with a hole in the roof, a feature observed by early ethnographers among many of the Plains tribes. Nevertheless, the ceremony holds some significance for the Gros Ventre and became central to the continuation of their cultural practices (Wissler 1916).

The social network of the Gros Ventre was mostly separated by gender and age. At the age of 15 or 16, boys were encouraged to form together into groups of friends and pledge themselves to either the Star or Wolf moiety. This decision was completely up to the group of boys and binding for life. The members of a moiety were bound to help each other in all aspects of life (Flannery 1953). After a moiety was chosen, a boy would pledge himself to an age specific group known as the Fly Lodge. This was the first of a series of age-group lodges that the boy would progress through as he grew. Various spiritual and social tasks had to be accomplished to progress from one lodge to the next. Membership in many of the lodges required the potential member to sacrifice property or give gifts. A man’s wife was an important part of this process as a lodge’s power was transferred from a sponsoring “grandfather” of a lodge, to the initiate’s wife, who then transferred it to him. This grandfathering process was an important part of the Gros Ventre society. Religious practices, ceremonies, and supernatural power were sought out by a person from an older male of a specific lodge but in the opposite moiety of the initiate. The grandfather and his grandson practiced reciprocal gift giving. The two men and their wives were to treat each other with great respect, avoid fighting, and fulfill any favor asked (Cooper 1957). Gift giving and assisting the less fortunate is an important part of Gros Ventre life. Gift giving and self-sacrifice are the fastest and most important ways to advance both politically and religiously (Fowler and Flannery 2001).

Prestige and honor were acquired through wealth, generosity, and bravery in battle or in hunting. Historically wealth was mainly associated with horse herds and success in trade. The latter often led to men marrying more than one woman to increase the number of buffalo robes a household could process and then trade in a season (Flannery 1953). Battle honor often came from stealing horses (especially tethered ones), taking scalps, killing, or touching an enemy, taking a weapon from an enemy, or assisting a comrade in battle (Hatton 1990). The more prosperous a man and his family were, the more people would likely form a band around them and share in the wealth.

A bandleader had influence on decisions concerning movement of the group but had no direct authority over any other family or band member (Flannery 1953; Curtis 1907-1930). The Gros Ventre tribe has an oral history concerning a “head chief” that over saw tribal councils. Unlike many other Plains tribes, the Gros Ventre Chief retained more power and control over the tribe. This was due in part to the influence of the Soldier Band, a group known for its strict discipline that was responsible for carrying out the orders of the Chief (Fowler 1987:31). Early dealings with the U.S. government, however, were carried out by a spokesman, and not a “head chief” (Flannery 1953). (Phillips et al. 2005:85).

Gros Ventre lived in tipis at the time of their initial contact with Europeans. The tipis were constructed using a three-pole foundation method. The average tipi was constructed of 14 to 17 skins although a prominent man and his family may have a tipi made of 25 or more. Tribal bands were known to arrange their camps in either long parallel lines of lodges or in great circles. The latter was used primarily for ceremonial gatherings of the tribe (Hendry 1907, Flannery 1953). When European trappers met the Gros Ventre in 1772, the tribe was noted as being expert bison hunters using the impounding method. This involved driving a herd or portion of a herd into a large corral. The tribe was known to use drive lanes and horses together to direct the bison into the corrals. Once the bison were inside the corral, they were speared or shot with arrows. The tribe was noted to be expert horseback riders using buffalo skin saddles with stirrups, and hair rope bridals. The first impressions of Europeans regarding the Gros Ventre were that the tribe seemed to have had horses for at least a generation (Hendry 1907). Horses were likely acquired from neighboring southern tribes, possibly through trade with their Blackfoot allies or through raiding the Crow and Sioux tribes. As well as their well-developed equestrian culture, Europeans accounts also noted baked clay vessels among the Gros Ventre. The Gros Ventre people were also familiar with European trade goods and firearms well before initial contact. Specific structures used by the Gros Ventre, including the multi-sided lodge built for the Grass Dance, were common among other Plains tribes including the Blackfoot and the Assiniboine (Wissler 1916).

Additional information regarding the Gros Ventre may be found in Kroeber (1908); Curtis (1907-1930); Cooper (1957) and Flannery (1953); and Hatton (1990). Horse Capture (1992) includes interviewed accounts from oral histories and cultural preservation efforts.

There is little evidence that the Gros Ventre spent substantial time in northeastern Wyoming. Gros Ventre territory was traditionally located in Saskatchewan, Canada and in northern Montana. Although the tribe was pushed south towards the end of the eighteenth century due to pressure from neighboring tribes, it is generally believed that this southern movement did not extend as far south as northeastern Wyoming. It is possible that some bands may have ventured into the basin, such as while camping in Crow territory in the 1880s, but these activities are not well documented. See Figure 9 for historic territories occupied by the Gros Ventre; note that these may not include all areas used by them.

TRIBAL RESOURCES

Gros Ventre Tribe

Fort Belknap Indian Community

656 Agency Main

Harlem, MT 59526

406.353.2205